It’s no secret that pedestrian fatalities and serious injuries have been rising in our cities. As more people explore active transportation options they are coming into conflict with vehicular traffic. A recent article on USA Today shows that this is a real problem and it is reaching a new level of visibility in the debate on transportation in the US.

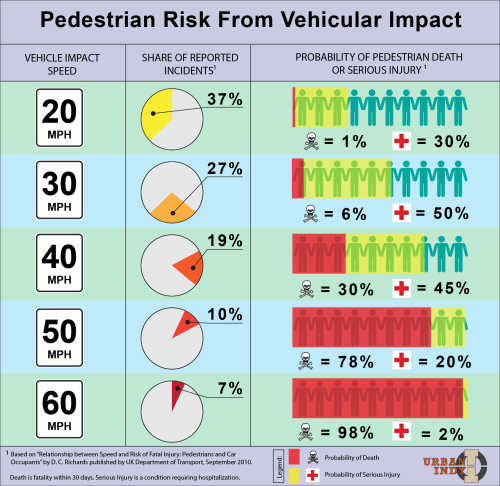

Most people understand that the faster a vehicle is driving, the more dangerous it can be for pedestrians and people on bicycles. Risk is a combination of probability and consequence, and the data in the chart shows a surprising increase in the risk as the vehicular speed increases above 20 mph, as shown in the figure.

This data is well known amongst traffic engineers, and it causes them to design streets in a way that I don’t approve of. Instead of designing streets that encourage drivers to be more aware of pedestrians and to drive slower, they isolate cars into traffic sewers and funnel them through the city at high speeds. The problem is that this cuts up the city, street by street. Pedestrians have only the option of staying on their own block or sprinting madly across several lanes of traffic. We need a better system, one that recognizes that there are places for traffic segregation and there are places for traffic integration.

This isn’t as difficult as it sounds. There are many successful models for building communities which are safe for pedestrians but preserve access for vehicles. You can look to the dutch “Woonerf” or “Shared Space concept.” The British have their own “Home Zone” initiative. But you can also find great examples here in Indianapolis. Our own Monument Circle is a fantastic place to see cars and vehicles negotiating space safely, and the finished Georgia Street is going to be a model for other cities for many years to come.

The examples above are great for low speed interaction between cars and people, but we also have some great ideas when it comes to managing high-speed traffic issues. The Cultural Trail is designed to move a large amount of people on foot or on bike through downtown, and it really elevates active transportation to the same quality and accessibility that vehicles have.

These local examples show that there are two effective strategies for reducing pedestrian risks:

- establish pedestrian zones where cars and people interact at very slow speeds – do this for both commercial and residential areas with local traffic

- establish arterial zones where cars and people are segregated – give people and cars separate facilities where the speeds are too dangerous for mixing

great post and graphic. This concept applies at many different levels of government as well. Unfortunately, INDOT applies the worst concept for pedestrian and even vehicle safety. Along with roads engineered to reduce speed, there is percieved items that can generally reduce speed. INDOT realizes the danger a high speed vehicle can have to pedestrians, property and even the car itself, so instead of working to reduce speeds to increase saftey for all, they widen road lanes, cut huge straight-aways, purchase and clear enourmous amounts of ROW all with the idea that any items near these roads would be dangerous to a fast car, I argue the car is dangerous and we should be working to reduce the speed of the vehicle. All INDOT does is make people drive faster becuase they percieve little conflict or obstruction. This is especially unfortunate when it comes to INDOT ROW through towns or cities. Pedestrians are tossed aside and development and land use shows it.

I am told all the time that it is dangerous to ride a bike on the street because a car may hit me. First of all….duh, but more importantly, it should not be dangerous to ride a bike. Think about it. The danger is the vehicle, the cyclist is vulnerable.

It is not a right to drive fast, nor is it responsible. Your graphic clearly shows the probability of death with increased speeds and this applies to a motorist as well. It shocks me that we promote a situation where death is essentially imminent.

From the end of the post:

These local examples show that there are two effective strategies for reducing pedestrian risks:

establish pedestrian zones where cars and people interact at very slow speeds – do this for both commercial and residential areas with local traffic

establish arterial zones where cars and people are segregated – give people and cars separate facilities where the speeds are too dangerous for mixing

I’m not sure if I understand # 2 properly. I don’t want to put words in your mouth, but I read that to mean that you are suggesting that it’s acceptabe that arterials allow vehicles to flow at speeds that makes these corridors inhospitable for pedestrians and bicyclists to safely cross or enjoy traveling along. As I think you alluded to earlier, limited access freeways are where vehicles should be able to flow freely and quickly, but there is no place for speed limits above 35MPH along urban arterials (I mean urban to mean urbanized vs. rural, thus including typical “suburban” areas in with urban). In fact, in the older parts of the City, I would suggest that speed limits shouldn’t exceed 25 MPH.

I agree, our cities would be much better off and safer if we could design our streets for speeds less than 35mph. 25mph would be great for the denser parts like the old city boundaries.

But yeah, the segregated but equivalent facilities should be available to offset the advantages of urban freeways. The Monon trail is a good example, but I would change it so that trail users were given the right-of-way at intersections.

I am glad that Urban Indy decided to cover this topic. The article identifies two types of zones – arterial and pedestrian. It seems to me that Indy has a major problem with this distinction. Indy needs to define which streets are to be considered arterial and which are not. Bike lanes, and by extension cyclists, are unfairly taking taking the brunt of backlash because the City has failed draw this distinction. This distinction is helpful in changing and shaping the discussion away from an us (cars) against them (bikes).

The distinction problem is most easily observed when people discuss the new bike lanes on Broad Ripple Avenue (“BRA”). Prior to the installation of the bike lanes, BRA was divided in a pedestrian section from College to approximately the Monon trail and an arterial section from the Monon to Keystone. Those individuals that complain of congestion and delay caused when the new bike lanes were installed seem to consider BRA to be arterial. On the other side are those individuals that see benefits in reduced vehicle speed and traffic calming and thus seem to consider (or desire) BRA to be a pedestrian environment stretching from College to Keystone. The unintentional (thought not unforeseeable) consequence of the BRA bike lanes has been to push frustrated motorists onto the low-speed side streets where they speed and run stop sides in their rush to get to Kessler.

In light of the information in this article, the lack of distinction places cyclists at risk of serious injury and death when bike lanes are routed along major arterial streets. The best example of this is Allisonville Road, with a speed limit of 45mph along which motorists routinely drive 55mph. At 50mph, there is only a TWO percent chance of a pedestrian avoiding a serious injury or death in the event of contact. The City must understand that bike lanes and high-speed arterial roads are simply incompatible. Bike lanes will not calm traffic if there is not already a low speed limit and enforcement of the speed limit.