In the summer of 2018 I found myself sitting in a room with a small number of other people, making decisions about how land in Marion County should be used. I’m a computer person by trade with no background in land use planning. How did I end up here?

The Impetus

The Long-Range Planning group in Indianapolis’ Department of Metropolitan Development had a challenge: Tasked with not only updating the balkanized and aged Marion County Land Use Plan, but in keeping with the vision of Plan 2020, which includes enabling the broader community to bring their expertise and interests to the task, how were they going to both produce a cohesive, modern plan, and find a way for lay people to contribute? Plan 2020 is a partnership between Indianapolis city government and community partners. It stitches many existing individual plans, ideas, and initiatives into a broader, cohesive whole, providing a framework for coordination and collaboration to realize the community’s collective vision. Rigid, prescriptive plans become out-of-date quickly as society and needs change. The Long-Range Planning group was tasked with creating a new, flexible Marion County Land Use Plan, not in isolation, but with the input of lay people who wouldn’t necessarily know what land use planning is.

Providing the right tools

The first step was to lay the groundwork for success by building a common, thorough, flexible language: The Marion County Land Use Plan Pattern Book. A land use plan describes a vision for how space is used. How much of our city should be residential? How much should be parks? Offices? Industrial? What’s allowed to be near what else? What’s appropriate near a school? Near a river? While zoning laws specify current uses, a Land Use Plan envisions an ideal future. In order to create and document that vision, they created the Pattern Book to give the staff and community working on the plan a common language to describe various uses of the land without being so prescriptive that the result was too brittle to be effective.

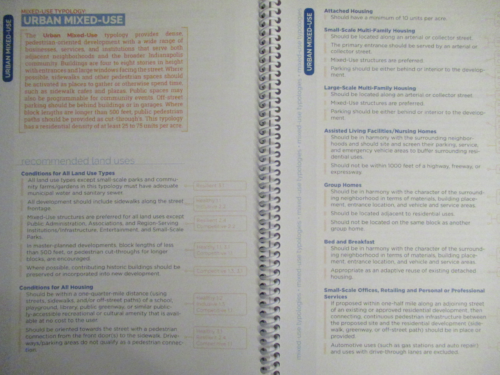

If you envision the buildings in a city or county, how many different types of buildings do you envision? And how many different types of spaces that don’t have any buildings do you envision? The Pattern Book first identifies these various land uses — the different types of buildings or non-building spaces one might envision — then identifies the various typical combinations of these land uses that are found together, calling these combinations Typologies. So, for instance, the land use of detached housing would be found in multiple Typologies, such as the Rural Neighborhood Typology, the Suburban Neighborhood Typology, or the Traditional Neighborhood Typology, but rarely in the City Neighborhood Typology, and practically never in the Heavy Commercial typology. Likewise, a Structured Parking land use makes sense in the Core Mixed-Use Typology or the Regional Commercial Typology, but not in a Suburban Neighborhood Typology. Further, within a Typology, a land use might be recommended with limitations. For example, a Structured Parking land use in the Core Mixed-Use Typology is recommended to include retail on the ground floor.

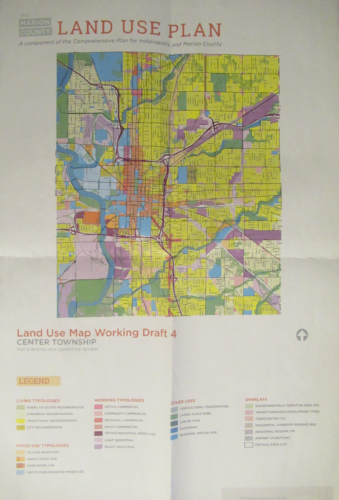

The Pattern Book uses thirty different land uses crossed with fifteen different Typologies to detail what uses are or aren’t recommended in different contexts. These Typologies are grouped into three broad categories: Living Typologies (Rural or Estate Neighborhood, Suburban Neighborhood, Traditional Neighborhood, City Neighborhood), Mixed-Use Typologies (Village Mixed-Use, Urban Mixed-Use, Core Mixed-Use, Institution-Oriented Mixed-Use/Campus), and Working Typologies (Office Commercial, Community Commercial, Regional Commercial, Heavy Commercial, Office/Industrial Mixed-Use, Light Industrial, Heavy Industrial). In addition, the Pattern Book uses seven different types of Overlays, such as Environmentally Sensitive Area or Airport Vicinity, to provide additional recommendations within each Typology.

A land use map based on this Pattern Book, then, divides the map into a layer of adjoining Typologies that could be further categorized by a separate layer of Overlays. A particular area, for instance, might be categorized into the Light Industrial Typology, but also have the Environmentally Sensitive Area Overlay applied. In that case, if a requested variance or rezoning were to take place, whoever is considering whether or not to approve the variance or rezoning would use the recommendations for the Light Industrial Typology and include the recommendations within that Typology for the Environmentally Sensitive Area Overlay that are specific to the Light Industrial Typology. Among these recommendations, for instance, is that while Small-scale Offices, Retailing, and Personal or Professional Services are still allowed as a land use, any development impacting wetlands or high-quality woodlands should include a one-for-one replacement of such features. The Overlays add potential extra guidance for each land use within each Typology.

Power to the People

With the Pattern Book in hand, the Long-Range Planning staff were able to meet their first challenge: Making a draft of a cohesive, modern land use plan for Marion County that uses a comprehensive and readily understood pattern language. The second challenge, though, still remained: How to not just engage the community, but equip community members to effectively bring their interests and local expertise to bear? The answer to the second challenge was the People’s Planning Academy.

The People’s Planning Academy, perhaps uniquely across the United States, endeavored to significantly increase the planning capability of a swath of lay citizens through direct training. A six part curriculum was developed and delivered by a combination of Long-Range Planning staff and a variety of collaborators from within and without Indianapolis government. Topics included the history and purpose of land use planning, the pattern book, how land use planning can support the four building blocks of Plan 2020 (A More Resilient City, A Healthier City, A More Inclusive City, A More Competitive City), and how to use the Land Use Plan Pattern Book. One could attend the six classes in-person, see them broadcast on TV, or view them online.

I was quite new to the process and found the information rich, useful, and sometimes sobering. The People’s Planning Academy was the first place where I learned about the discriminatory practice of redlining, started in 1934, which tilted home mortgage lending heavily towards mostly predominantly white neighborhoods, as well as the even more overt, earlier racism of covenants that restricted who was allowed to own property by race. I was happy to see the training be open about our unpleasant past. We have to know about these things if we’re going to find ways to address inherited inequity. I don’t claim to have answers for how to address that inequity and the People’s Planning Academy, beyond being open about the problems, didn’t explicitly offer solutions, but the Plan 2020 building block ‘A More Inclusive City’ does at least point the planning process in the direction of looking for equity.

The People’s Planning Academy succeeded, providing more than a hundred lay people with the ground work they needed to fully participate in the planning process. With this success the second challenge had been met, enabling people to use their newly gained knowledge to express their ideas and opinions in the language of the Pattern Book, but the work of actually bringing in all of the input from the community still needed to be done. This work would include soliciting opinions from everyone in the county and inviting the graduates of the People’s Planning Academy to join the township-specific Stakeholder Committees who would review the draft plan and finalize the draft before submitting it to a formal hearing.

Making a Final Map

The draft plan was put online so that anyone in the community could provide their opinions, and many presentations and office hours were scheduled around the county to explain the draft Land Use Plan and solicit further opinions. Long-Range Planning staff took these online and in-person opinions and incorporated them into the plan before presenting the draft plan to the Stakeholder Committees, one committee for each township in Marion County. The Stakeholder Committees had voting members appointed by various governmental agencies and non-voting members invited from the People’s Planning Academy. I was a member of the Center Township Stakeholder Committee.

We met three times, once each in June, July, and August. A professional facilitator ran the meetings. We were carefully instructed that these were open meetings, so all discussion of the Land Use Plan by committee members must be done at the committee meetings, where everyone could partake. We were encouraged to reach out as much as possible to the rest of the community to solicit their input. Many of the committee members were active in homeowners associations and other local organizations. In each meeting, Long-Range Planning staff presented the current status of the Center Township portion of the Land Use Map, pointing out changes that had been implemented based on committee and other input. Committee members were invited to review the Land Use maps and bring up any area of the map for further discussion.

Despite the training, the difference between zoning laws and land use planning had to be repeatedly reinforced. Zoning is the laws about what is allowed. Land use planning is about what would be considered ideal. Plans don’t change what’s built or allowed today. Plans inform future decisions. Plans are policy, not law. Where planning often comes into effect is if there’s a request for a variance of use to the zoning of a parcel. Planning becomes one of the inputs to whether or not the variance would be allowed. The Metropolitan Development Commission must consider, amongst other inputs, the plan. Note that planning does not have to be considered when there’s a request for variance of development standards, only for a request for variance of use. Planning would also be considered if rezoning were being considered, either broadly, or for a particular parcel. And for places that don’t yet have zoning, a plan must first be created. So planning doesn’t come into effect until someone is looking to make a change to what’s allowed.

With these differences in mind, committee members could more easily get past the confusion of what it would mean to recommend a different Typology for an area of the map then how that map was currently used. Discussions about changing the map broadly fell into two categories: The map should be updated to reflect the actual use, or the map should be updated to reflect a hoped-for better use in the future. There were many straightforward changes proposed and easily accepted, as people familiar with an area would point out how the draft Land Use Plan could better align with what they know was already going on or with how they thought an area would or should evolve. In a few cases the discussion involved many people with differing viewpoints and consensus took a lot of back and forth to reach. One that I recall was whether or not an area along east Tenth St. that currently has residential housing should be protected with a Residential Overlay, or should be allowed possibly to evolve into more of a commercial area. Another was discussion about major intersections along East Michigan St. and East New York St. and whether their Typology should be one that allowed a land use that included gas stations or not. The group eventually reached consensus on these issues, but these were not obvious choices.

The Finish Line and the Future

Once the committees reached consensus, the voting members voted to finalize each Township map and then each Township map was, or in some cases will be, submitted to the Metropolitan Development Commission for a hearing. I and a few other committee members attended the hearing and spoke in support of the Center Township Land Use Map, which passed with no dissent. Attending the People’s Planning Academy and participating in the Center Township Stakeholder Committee were rewarding experiences for me. I learned much, enjoyed being involved, and feel like we helped provide a quality Marion County Land Use Map. I will admit to some concern about just how much this Land Use Map will actually affect decisions. As noted, it’s only used when someone is seeking a variance of use or to change or create zoning laws, and even then it is only one of multiple inputs used. I would like to know just how much the Land Use Map gets used and, further, abided by over time. Still, I’m glad we have it, and I’m glad I got to be involved.

Most people who live in Indianapolis and who have invested their money in their single-family homes have no idea what the urbanism fanatics and developers have in store for them. Most don’t agree with Agenda 2020, and don’t even know about it. It will bring more tall, ugly, out of place modern-design apartment buildings constructed of cheap materials into neighborhoods, all containing the obligatory “mixed use” fad. What you’ll succeed in doing is driving most of us single family homeowners away to other counties because taxes will be so high to cover TIFs, tax abatements, grants and subsidies to developers, subsidies to professional sports teams, the endless money pit to pay for the failed BRT system, and Indianapolis schools will continue to suck.

It is interesting that you describe the BRT as a “failed†transit system even though it is still under construction well over a year from operating—your divination skills are wonderous, Sorceress. As for subsidies to professional sports teams, they have been occurring for well over 30 years and have nothing to do with the Marion County Land Use Plan. IPS is a struggling system, but it has been for decades, and again, it has nothing to do with the Lamd Use Plan. Also, I would not say all the public schools in Marion County are bad, in fact, some are quite good. Mixed use buildings in Marion County have existed since the inception of the county, so I would hardly call mixed use development a “fad.†You seem to be throwing out everything including the kitchen sink, even though much of what you are ranting about has nothing to do with zoning. You seem unhappy with Marion County, and I would suggest you do move, if you haven’t done so already.

Thanks for the positive feedback!

Lol @ Agenda 2020.

I noticed that too. That’s art.

“Mixed use fad.” Heh. Have you been to Europe?

or literally any other country on the planet…

Nice recap. It was a great process to participate in. We were able to give feedback to planners on the front end, instead of the back end as is custom.

The Marion County land use plan is far from a revolutionary document. It is fundamentally incremental in its design. There are some that might think that it doesn’t go near far enough, and yet there will also be others who think that any slight move in an urban direction is too far for Indy.

I personally think we could do more than gentle nudges, but will also easily accept this as a good step forward.

Andrew, I’m glad you were able to go through this process (and glad the City is asking for help).

That said, does anyone else think Indy is somewhat obsessed with planning efforts? How many are going on right now or recently completed? Land Use, Thrive, Indyparks Master Plan, White River Plan, etc.

How many plans can one city need? How much money are we spending on planning that could be better spent on implementation?

I know that the Marion County Land Use Plan avoided areas that had recently had separate planning done. I’m not as certain, though, of how the Land Use plan relates to the others you mentioned.

My guess is that any sort of a parks plan would be less about _where_ parks should be (as the Land Use Plan would) and more about what should be in each park, but that’s just a guess. For the White River, I think it’s useful to really focus on that feature in a way that wouldn’t have happened in the Land Use Plan, both because the scope of the White River Plan presumably goes beyond just land use and perhaps also because the constituents needed for the White River Plan are more specific, with interests directly related to the White River.

I’m a bit less sanguine about Thrive. I went to one of the meetings, and while I was impressed with the questions being asked, I didn’t get a strong impression that it was going to lead to anything. I saw a later report about Thrive and wish I’d taken more care to retain what it said.

I do know that the general aim is for all of these plans to be part of a greater whole — Plan 2020 — but maybe there is room for them to be more closely integrated. Hard for me to say. There’s too much I don’t know about the various plans and there purposes.

A related, relevant question is: when do we hit “planning fatigue”? I’ve exercised citizen involvement in three of the four plans you mention and completely avoided Thrive precisely because it seemed duplicative.

Meanwhile, I’m not aware of an economic development plan for the county…

I’m there already.

Just hitting my inbox this morning was an update on the upcoming “Action” phase of the White River Vision Plan, which doesn’t sound like action at all:

“Phase 3: Action will include detailed recommendations for implementation of the plan, ways to support specific projects, and strategies for securing funding for completion.”

Yeah. “Action” (and for that matter, “plan”) means something totally different in professional planning circles than in the rest of professional life.

The Land Use Plan is part and parcel of the future of Marion County and will be a factor in shaping those features that attract and detract from the quality of life and desirability of living here. Such considerations include poorly performing (overall) schools, high taxes, especially relative to nearby counties within reasonable driving distance that have good schools and ever-increasing home values, endless subsidies and sports palaces for professional sports teams paid for by taxpayers, as well as land use controlled by urbanism fanatics and developers, driven by the profit motive and desire for as much public assistance as they can get.

The goals of developers and urbanism fanatics are not shared by most people. Millennials have discovered that paying several thousand a month for an apartment is not a good investment, because the money could go toward building equity in a starter home, in which they could have a yard for the dog, a garage for the car, and a place to grow flowers and vegetables. The Coil in Broad Ripple is a good example. It was just sold, even though it has been open for less than 2 years. There have always been plenty of vacancies.

As to the BRT system, the likelihood of success is very low. Most people in Indianapolis don’t ride a bus and don’t want to. Indianapolis is too spread out for any rapid transit system to provide substantially-faster commuting than traveling by auto, which pokes a hole in the “Indianapolis has always been a transit city” balloon. There is no way to get Downtown without passing through residential neighborhoods, which limits the speed of any public transportation system. The BYD electric buses failed their first real-world test, and were returned by Albuquerque, which is planning to file suit. Nevertheless, in its consistent pattern of ignoring reality and what is in the public’s best interests, IndyGo presses on. Because the ridership projections will never materialize, IndyGo will need ever-increasing subsidies. Eventually, due to even higher taxes, it won’t be worth living in Marion County any more.

Natacha, while some of your points may be (or turn out to be) true, the fact that the Coil was just sold is actually a sign of its success.

The developer achieved what they wanted, and the investor who bought it is getting something they obviously value at tens of millions of dollars (and something that has appreciated since its opening two years ago).

Some of the things you mention are matter of opinion or at the least difficult to prove. The success of the Coil is not up for update, though, no matter how you try to spin it.

As to The Coil, a friend of the Brownings reported on Neighborhood Next Door that one reason it was sold was because of the vacancies. If you look at The Coil’s website, you can gauge for yourself whether it has lots of vacancies, based on the reported number of units available. Not exactly a smashing success. Bear in mind that this project was passionately opposed by the BR community and businesses, and that suit was even filed to try to stop it. While I don’t shop there, people I know who do go to Fresh Thyme tell me that it’s not very busy. I view this project a bellwether for the urbanism fad in Indianapolis. One question no one is asking is how much taxes can keep going up before people who can afford to will move out of county. The more TIFs, grants, tax abatements, IndyGo and IPS tax increases, and shoving unpopular modern cheaply-constructed apartment buildings into residential neighborhoods, the less desirable Marion County.

I bet the investor who bought The Coil is kicking themselves for not consulting “a friend of the Brownings on NextDoor”, rather than their sophisticated financial projections and due diligence by a series of lending professionals.

“how much taxes can keep going up before people who can afford to will move out of county”

And yet – in spite of the Red Line, tax hikes, and continued urban infill – here you are.

Well pack your bags and quite wasting our time.

The goal of the Coil and other apartment buildings like them has always been to build them, lease them, and then sell to an investment group. The occupancy rate was over 90% at the time of sale as noted in the press release. This is not casting a value judgement on this business strategy but from the developers point of view, it was a success. Presenting it as a business failure is dishonest.

You should start by presenting your arguments in an honest way and then maybe we could have a more productive conversation with you.

Paul, the 91% occupancy rate was stated in the listing, but anyone with access to a computer could check on the number of available units, which places this figure into serious question. Then, there’s the Brownings’ friend who posted on Neighborhood Next Door that units weren’t exactly selling like hotcakes, which is why it was sold. On Yelp, one renter displayed photos of what he claims was mold growing on the ceiling of his unit. I claim no first-hand knowledge, but people haven’t been knocking down the doors to rent apartments at The Coil,

You state that the goal of The Coil was for developers to build and sell, but was this presented at the various BRVA meetings and zoning hearings? What do the taxpayers, whose lending power contributed to the TIF, get out of the deal? An ugly, out of place modern-design building that detracts from the small town ambience that had always been part of Broad Ripple’s charm.

So the real estate listing says 91%, the press release for the sale says over 90%. The selling price (over $40 million) suggests that the building had a very healthy occupancy rate. But some random lady says she heard otherwise on Nextdoor and you believe her. That is really something.

It’s the Focks Nooz effect. 🙂

If the Coil cost $37M in 2017 (https://www.ibj.com/articles/62836-debut-of-37m-coil-kicks-off-broad-ripple-apartment-flurry) and sold for over $40M recently, that’s about a 10% rise in one year–not bad at all for a market like Indy, where land values appreciate slowly.

Neighborhood Land Use Committees deal with zoning issues, not who might own a building in the future, or, for the most part, how a building might be utilized in the future.

Since this building has one year leases and they probably fill open units 3 months before they are set to be vacated, that means at any given time, there are quite a few spots to fill as folks move out. That really has little to nothing to do with the vacancy rate. Call me when rents start dropping instead of steadily climbing as they have been for almost 10 years.

Saying “most people” over and over again Natacha does not make it true. Get some data to back up your assertions and then I will give them some consideration. Otherwise try speaking only for yourself.

If Natacha lived in Chicago, she would still be arguing with Daniel Burnham who more than a century ago famously urged people there to “make no small plans.â€

After people on Neighborhood Next Door started looking at the number of available Coil units, because they didn’t believe the claim of 91% occupancy, they took down this information from their website.

It’s called Nextdoor. Get it right.