Back in January I hypothesized about what BRT along Washington Street might look like, envisioning the future from 30000 ft of what service might look like and how stations might look. Since then, I have put on my engineering hat to think about how we plan for the stations along the route. Additionally, how might those stations look? Would they resemble covered shelters like what we currently have on the sidewalk? Would they resemble “island” stations similar to what we might find in Cleveland along the Healthline?

To narrow down these answers, we must first consider some assumptions. Remembering that each transit trip starts as a pedestrian is one key assumption in determining service. We must be able to safely get to the bus as it pulls up. We must feel safe as we wait on the bus. We must be able to stay dry while we wait on the bus. These sorts of things seem like forgone conclusions when it comes to planning service but as we know, Â many transit stops in our city not only lack a shelter, but also lack a sidewalk to wait on the bus. Offering a premium transit service will depend not only on how fast or frequent it is, but how users interface with the bus.

Service Assumptions & Examination

Defining the service level is something that we can easily plan ahead of time using hard numbers and reach credible and comparable conclusions. Will buses run in mixed traffic or in dedicated lanes? Will they run in some portions of the line in mixed traffic and in dedicated lanes in other portions? How much does current frequency affect people’s propensity to use the service and would an increase in frequency of the current service result in increased ridership and thus longer travel times due to more stops? We already know by FTA regulations that 50% of the bus line must be dedicated to buses during rush hour. It makes sense to assume much of these lane miles will be dedicated in areas where stations will be located since they offer the most opportunity for friction (slow down related to external factors such as parked or turning cars) where the dedicated lanes will create advantages for the service, and thus REAL value. However, will these lanes be located next to the sidewalk or will they be located in the median? What criteria should we use to establish these assumptions?

According to the Transit Cooperative Research Program (TCRP) Report 90,

“… using bus priority treatments should reduce both the mean and variability of average journey times. A 10 to 15% decrease in bus running time is desirable to justify investment.”

This is one method of quantifying the current average travel time to what the target travel time should be. The chosen treatments will define how much of an improvement that we can expect to get.

Route 8 East Side Current Service

For the rest of the post, I will be focusing on the East Side of Route 8. So what does current service look like?According to the posted Route 8 schedule (and it varies depending on what time of the day you choose), an inbound trip from Meijer on the east side to downtown is roughly 9.8 miles and takes approximately 45 minutes resulting in a rough average of 13mph. Â Several assumptions define this service such as:

- Current service is considered local stop

- Washington St is a mixed traffic automobile corridor

- No bus signal priority

- Posted speed limit is 35mph

We now have a basis for comparing improvements. A 10%-15% improvement over that would 40.5 – 38.25 minutes. Figuring out how to get there takes some math, but is 38 minutes compared to 45 minutes a significant decrease in travel time to travel the corridor? Would simple changes to the current service such as bus lanes at traffic lights be enough to net these sorts of improvements? An even more introspective look at how planners got to the current schedule would conclude that there are 35 potential traffic lights along this same stretch, a certain number of people are willing to use the bus given 30 minute frequency (now 15 minutes throughout the day with 2013 service improvements) and population density and demographics drive people to use the bus because they have to, not because they want to.

Perhaps solving the question of desired service results in another question. What should we be accomplishing with this project? Is a significant reduction in travel time really the sole criteria for deciding to invest? Is a 5 to 7 minute savings in time over current service really worth the millions in investment? What if we looked instead at neighborhood quality of life as a way of judging success. Would increased economic investment be a good indicator? Would a service providing travel times that are similar to the current service with more frequency but resulting in Transit Oriented Development (TOD) be worth the investment? Should bringing people back to these old neighborhoods, which are bleeding population year over year, be another critical criteria of this project? Indeed, observed increases in pedestrian activity would be one way to measure that and leads us to the next level of discussion.

Corridor Land Use Planning

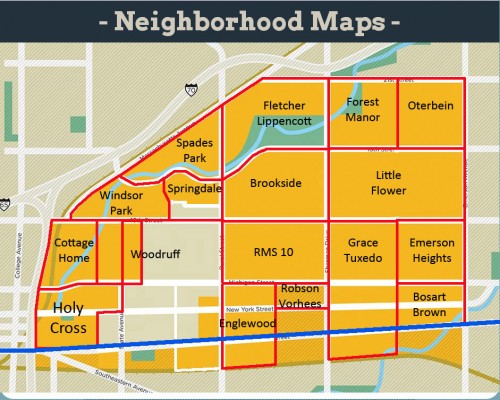

These questions open up the social side of the project. Neighborhoods along East Washington are starved for investment. Sure, there are pockets of success such as Irvington, however we must consider what the other not-so-successful neighborhoods along the line want. While transit is not a sole method of achieving neighborhood growth, it does represent critical centralized planing and investment in the corridor and is a prime opportunity for other neighborhoods and CDC’s to take advantage of implementing a path to success. We saw this sort of catalyzed effort on the near East Side leading up to Super Bowl 46 and few would question the improvements that we have seen in some of those neighborhoods. Could the Blue Line also lead to similar improvements?

Conclusions

So, lots of questions and not enough answers right? A lot of how this project moves forward will depend on how we decide the answers to these questions. Will we decide that reducing automobile speeds is key to sparking interest around these nodes? Will speeding up the service by optimizing the bus travel lanes become top priority at the expense of automobile level of service? If current service were simply maintained and service frequency adjusted to 7.5 to 10 minutes all day, would the resulting increases in ridership demand that we should have blocked off more space for dedicated lanes?

What do you think?

I think the Washington St. ROW is too narrow to give two lanes plus the occasional median island to exclusive use by BRT.

In addition to being a heavily used transit corridor, it’s also a heavily used auto/truck corridor. In fact, it’s really the only suitable local east-west truck corridor now that the lanes on 10th, New York and Michigan have been narrowed.

This is why I have advocated for BRT to go on the Michigan/NY pair, at least west of Emerson. There’s a lot more ROW to work with, plus it puts the transit line in the middle of the people who will use it, instead of at the neighborhood edge. (There is only one block or less of residential use south of Washington and west of about Colorado.)

It’s not true BRT if there’s no signal priority. In that case buses are just going to fight the same congestion autos would, though there’s not that much in this area currently or as the areas Chicago’s looking to implement BRT (streetcars are a nonstarter there oddly for some reason). And I wouldn’t want to cross to an island station when the speed limit is 35mph with highway-width lanes.

Grand Rapids, MI, BRT station: http://groundlevelmw.blogspot.com/2013/06/under-construction-silverline-brt.html

Nice post Curt. One thing on travel time is that although the posted speed limit is 35 mph the buses aren’t traveling that when they are in motion. This is because the lane widths are currently 10 feet (the bus with mirrors is 10.5 feet). They tend to crawl more at 25 mph just tying to avoid sideswipes. Washington Street represents the portion of the IndyGo system with the most reported transit vehicle accidents for just that reason.

You should ask NESCO why they’re map is missing Arsenal Heights, St. Clair Place, & Willard Park. These are some of the neighborhoods that could certainly benefit from improved transit service as well as from private investment that could come as a result of a well designed public infrastructure project.

Oops. I meant their, not they’re.