What happens when a large section of a city threatens to become obsolete? Â That question came to my mind after hearing Indianapolis’ DMD director Adam Thies mention that he was worried about the future of Pike Township at yesterday’s We Are City Summit. Â I was fortunate to be invited to the event as a media member, and I left both inspired and looking for answers. Â Thies mentioned that most of the houses in Pike Township were built to last 30 years, and they are rapidly approaching that age now.

First, this is a look at Pike township’s buildings from 2012:

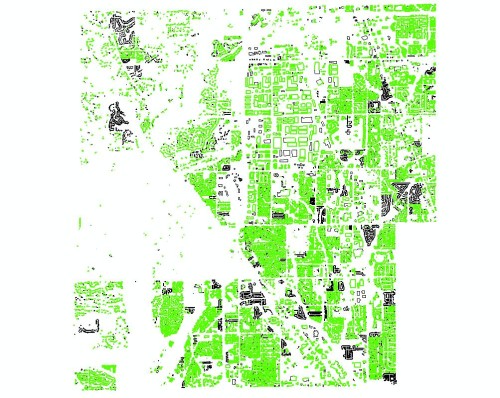

Now let’s look at the building outlines that were placed before 1996. Unfortunately I do not have access to house age data, but the building outlines are good enough for the purpose of this post. The older building lines are colored green:

Of course, this selection captures many older buildings that are not of the age that Mr. Thies was referring, so let’s drill down further to show the building lines that were built between 1986 and 1995:

A selection count shows that 11,187 of the 35,722 building lines in Pike Township were built between the years of 1986 and 1995, which accounts for almost 1 out of every 3 lines. That is a ton.

Not surprisingly, this is a heavily car-dependent section of town with few sidewalks along the major roads, but there have been some improvements there recently. Here’s a brief rundown:

- Michigan Road recently completed a long path along the west side of the street.

- Westlane Road was the second bike lane built in the city.

- 56th Street and 71st Street have each added a multi-use paths and bike lanes.

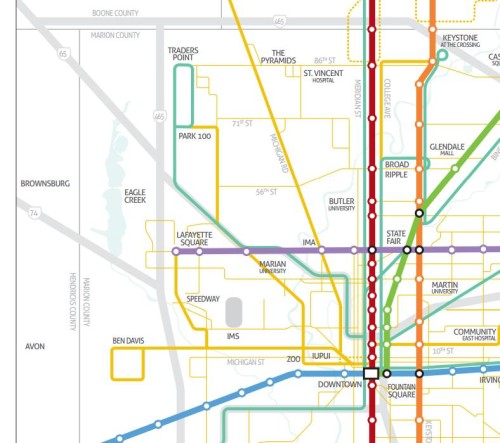

There are a few IndyGo lines currently, but they are a bit of a meandering mess:

This network would make a bit more sense if IndyConnect were passed. The same lines would be kept in place, but there would be more frequent trips along Michigan Road and from the Park 100 area:

This leaves us with some serious room for improvements. Running more buses along thoroughfares and completing the sidewalk and bicycling network are obvious future moves for the township, but of course the money for these projects will have to come from somewhere. In order to make Pike Township an attractive place to live in the future, however, the city will likely have to figure it out. The other option is slow decline.

I was reading the ebook Strong Towns by Charles Marohn which is basically a lightly edited compilation of his blog posts. He actually has a chapter about this:

“What is the future of the structures built during the Suburban Experiment? While it is unsettling for many to even consider, it is likely that a high percentage will be used for salvage material.”

Prior to reading the book, I just kind of thought, ‘Oh, after 100 years or so people will just restore them or tear them down for new ones.’ However, I started thinking about the “vinyl villages” that are prevalent in Greenwood where I grew up and most of those that my friends lived in were 10 years old in the 90s when I grew up there and they were already falling apart. I agree with Adam Thies that most of these buildings will be done by 30 years.

The bottomline is that it is shocking to think that a newish house built in the past 30 years could be worth less than the value of the copper wire, pipes, drywall, banisters, etc that make up the house.

You can read all of Charles Marohn’s Suburban Salvage article here:

http://www.strongtowns.org/journal/2011/10/10/suburban-salvage.html

Thanks a lot for posting this! I’m completely addicted. I am up in Carmel, and it’s interesting to apply the principles of Strong towns to booming Hamilton Co. right now. How can Carmel, Fishers, etc. not face the same challenges when growth slows that the inner burbs face today?

So Adam Thies believes that most of us who live in Pike Township live in mobile homes that have a limited life expectancy? By his 30 year life expectancy for a Pike house theory, which appraisers and lenders don’t share by the way, Pike houses should always depreciate in value. They don’t because if maintained those houses will last a lot more than 30 years. The houses in Pike by the way are not substantially different from those in other Marion County townships.

Yes, obviously he meant that literally, LITERALLY, every single house in Pike township is going to fall over at 30 years + 1 day and there is nothing you can do to stop it.

Back to reality, I took his meaning not that Pike houses were any different, simply that Pike has an large percentage of cheap housing approaching the end of its design life. I’m guessing the audience at these events are much more likely to live or work in Pike than Wayne, Decatur, Franklin, etc, and he knows this.

Chuck Marohn’s Strong Towns approach is nothing short of fantastic. I’ve gone back and listened to every one of his podcasts over the past few months and read quite a few of his blog posts, including the one you posted.

Inner-ring suburbs like Pike township really just the canary in the coal mine. The infrastructure ages and the housing stock falls out of favor for something shiny and new, but the area doesn’t have the versatility of a grid-based development pattern, which would allow it to evolve into something that’s still useful or productive.

Thies may have been a bit too conservative with his remarks, but he’s close to the target. Most homes built in the county in the latter half of the 20th century will ultimately prove to have a 40-50-year lifespan. They were not built to last; they were built to sell.

And Ogden is correct, also. The fact that a substantial portion of our housing stock is more-or-less disposable applies across townships, including a majority of the stock in Pike, Lawrence, Wayne and Warren.

In one sense, that’s a good thing. The poorly-crafted houses and infrastructure that tie us to the suburban experiment in these places will die off of their own accord in short order. That’ll make it easier to start from scratch.

While Thies may be drawing some reasonable inferences, it doesn’t seem like the most judicious observation to make public, considering the high-profile position in urban development. Paul Ogden is right–homes taken care of in Pike Twp (or any township, for that matter) should last well beyond 40 years. Is it really in the City of Indianapolis’ best interest to tar Pike Twp with the brush of obsolete housing? After all, huge portions of Pike housing (both inside and outside the beltway) were built in the 1960s and 70s, placing them fully within Thies’ depreciation index. But Pike still has many viable communities, again both inside and outside the beltway. And even well-built homes would deteriorate significantly in 40 years if left unmaintained.

David H, I wouldn’t be too sanguine about the expiration of these so-called poorly-crafted houses so we can wipe clean the “suburban experiment”. After all, the suburban experiment isn’t remotely close to dying out, and I have gotten to witness firsthand what happens when a community lets its low-cost housing fall into neglect. In Detroit, the less desirable 1940s neighborhoods like Brightmoor are now 90% vacant lots. It’s no longer a viable community, even with suburban (or even rural) density levels, and that’s not going to change any time soon. Detroit may be an extreme example, but it’s not a mentality we want to foist on other cities just because we have personal grudges against the settlement patterns.

I think something that gets confounded in all this is Unigov. Pike and Franklin mainly, but parts of the other donut townships as well, really should not be part of Indianapolis proper. They should have had different densities, they should have had different neighborhood profiles, and they should have had different goals than Center and the City of Indianapolis.

I know many people heap praise on Hudnut for the creation of Unigov, but personally, I’m not so sure. I think we traded short-term financial economies-of-scale for long-term viability. I would put the short-/long-term split at somewhere in the 40-60 year range and I think we are starting to see the cracks in the foundation. Specifically where I started thinking about this was when I was reading about the Rebuild Indy funds running out and how much of Indy is left without sidewalk and other basic quality of life infrastructure. If the parts of Indy outside the beltway were known as “Marion County”, I think people would have a much different feeling about moving there and feeling entitled to things like sidewalks, city water, and city sewers.

With Indy’s low density, it seems like eventually some of that outer area is going to have to be put back out to pasture and I think the stuff that Adam Thies was pointing out (along with Franklin which is probably newer than Pike) will eventually be to costly to maintain.

On a somewhat related note, I’ve heard talk about urban growth boundries (specifically, some talk between Mayor Brainerd and Sen Kenley at some transit hearings) and I’m fairly unfamiliar with them. Can someone give some idea how something like urban growth boundaries would work with a city like Indianapolis?

An Urban Growth Boundary (UGB) typically works best when you have pressure to grow outward in one or two directions because of natural feature limitations such as mountains or bodies of water. Yes, I realize we hear this excuse for a number of items such as transit and density. Ultimately, for a UGB to work, there has to be a significant product or difficulty with the area included within the UGB boundary.

Indy just simply can’t offer such an exclusive product that restricting growth would keep people within the UGB. I believe they would just relocate to the edges of central Indiana and commute in. Additionally, for a UGB to work, you need an extremely cooperative metro region, a body to review and amend the UGB and a decent system of TDR’s, Transfer of Development Rights. My guess is, very few of these would occur here.

If we want to discuss options for improved efficiency, I would suggest a USB. While Indy isn’t such a massive draw nor does it have limiting features to create the necessary conditions for a UGB, Indy does offer a large enough scale as a utility and infrastructure provider to potentially create an effective USB (Urban Service Boundary). I believe this would not only improve development patterns, but is actually a fair and honest approach to guiding growth. It seems almost all communities have now realized that funding infrastructure for a sprawled environment can’t be sustained. Even newer suburbs surrounding Indy are faced with a backlog of infrastructure needs. Ultimately, a USB is a recognition that funding can only support so much and thus the limitations.

I do realize a USB is a much softer approach to responsible development, but it also seems to relate to a free market better than many other approaches. If a developer would like to build outside of the boundary, they must provide their own services that would be covered within the boundary. The metro region could then focus on maintaining and improving what exists.

So basically USB would say, “Want city water/sewer/sidewalks? Stay within this boundary. Don’t mind well/septic/ditches? Build beyond the boundary.” I like this.

Do you think that Beech Grove and Speedway have better development patterns than Indy because of the boundary restrictions?

I haven’t explored these areas in depth with relation to this topic, but my guess is that they don’t. Enough services are generalized between the excluded cities and “Indy” that the benefit from one to the other is likely negligible.

The suburban experiment won’t die off. Either the productive class will demand better built homes in the burbs, or they will move to a city center, but will displace the consumer, welfare class who will be pushed to the falling apart homes in the former burbs. The productive class will never co-mingle with the welfare class, due to the vast differences in how each group lives, their morals, and values. I believe it is easy enough to go back to building all brick and stone homes, which will last decades with minimal upkeep. I’m starting to see signs of metal roofs in Indiana as well, which usually have a 40-50 year lifespan. Think of all the cars still sitting in junk yards waiting to be recycled. All the metal 2x4s and roof materials that could possibly be derived from all the scrap metal sitting around.

The suburban experiment will never die off…but the future of this experiment will become less sustainable. Time to start over with smart growth ‘suburbs’.

Last time I checked it was former Senator (then Mayor) Richard Lugar who who was in charge during the Unigov creation process, not former Mayor Hudnut.

Plus, I think that “poorly crafted” housing has a much longer lifespan than is being credited here. Housing stock survives as long as someone is willing to put some effort into continued maintenance (no matter how slipshod) whether that be 30, 60 or 100+ years.

I don’t believe Adam literally meant all of PT would implode in 30 years, nor do I think he was picking on PT. I would simply state that when making a point, you need something to illustrate it. PT just happened to be a good/bad example. That being said, after 30 years in many of these homes, the reinvestment required to bring it up-to-date often times outweighs just picking up and moving on. The home then begins a steady decline of less invested owners and potentially renters. Why stick around in an up and down neighborhood when you can move out to the burbs, get a mansion on the cheap (also built extremely cheap) and be relatively certain of added value and “better” schools?

When “making a point”, I would posit that exaggerating or using misleading statements might just undermine one’s credibility.

Thies was giving a presentation and keeping the audience engaged with crazy-but-true generalizations. I really don’t see how he mislead anyone with his statements. Lots of houses in Pike Township were poorly built and are reaching the end of their useful life. He never said all the houses or that they would fall down on the first day of the 31st year.

Perhaps I just don’t know what the “useful life” of housing types is? Sounds vaguely elitist and/or insulting.

I can no longer tell whether or not you’re trolling. Structurally speaking, are you really suggesting that the new houses people are building today for $100k are going to last forever? Or that the equivalent cheap houses built 30 years ago will?

It’s not insulting or elitist, those feelings are on you. I don’t feel insulted because I drive a Chevy (I do, actually), even though other cars are better quality, will last longer and have higher resale.

Even the classic old homes in Indianapolis take a tremendous amount of maintenance to have lasted their ~100 years. Not all of them made it. Not all of the cheap suburban housing will make it either.

Chuck, by definition, I think that if I were trolling, I would simply be dismissive of your remarks while criticizing your grammar (or something like that).

In fact, I just think that we aren’t speaking from the same set of experiences. To answer your question, no, I don’t think that housing of any caliber is going to last forever. But, I do think that housing exists long beyond its obsolescence, useful life or whatever other trendy urbanist concept you wish to apply. Why do I think that? Because they exist. Everywhere. Join me in a car ride around Marion County someday and I will show you, if need be. That they exist makes the whole idea that they are worthless (or will be) to be elitist (and insulting to those who continue to occupy said housing) to me. Many houses built after WWI weren’t meant to be used for 95+ years (and counting); many houses built after WWII weren’t meant to be used for 20. That said, how do those houses (which remain viable to this day in droves) differ from the vinyl village type homes being talked about here? And, if they aren’t (or are) all that different what makes the vinyl village lifespan such a crisis today?

To add to what Chuck said, there is a cost/benefit analysis to be had. At some point, the cost of updating or maintaining any house has to be weighed against the value that is derived from it.

When comparing an old house from the early twentieth century to the “vinyl village” house that was popular over the past few decades, there are some major differences. Brick vs slab foundation, lap-board vs vinyl siding, and hardwood vs carpet are just some indicators of quality of materials used. One was built to last; one was built to sell (as mentioned above).

Not to mention that the rise of the automobile and cheap gas made non-central locations such as Pike Township more desirable, but the resulting development patterns are going to be hard to cope with as gas gets more expensive and tastes for driving change. Center Township already has things in place (street grid, commercial nodes, walkable neighborhoods) that will make its future much more stable. Pike Township (and the other donut townships) unfortunately are a maze of cul de sacs which essentially force the ownership of a $10,000/yr piece of machinery to function.

Point being, the 100 year old houses are mostly concentrated in areas where 100 years ago, you didn’t need a car (mostly because cars barely existed). And while the old houses cost a lot to maintain, they also provide tons of value outside of their sheltering capabilities – proximity to sporting events, culture, shopping, etc.

ahow628, assuming that there is a cost/benefit that a homeowner need assess, what explains the continued maintenance of such housing past what an analyst might consider a poor economic choice? Something else must be an overriding factor not explainable by money. Plus, we need to divorce comparisons of incompatible housing types. Houses built prior to WWI were built better because the new owners could afford craftmanship. Homeownersship wasn’t in the cards for an overwhelming majority of Americans back then. Using those kinds of housing as your benchmark is comparing apples to oranges. Better to use housing build for more of a mass markeet after both world wars and to the late fifties/early seventies housing boom. As I mentioned to Chuck (above) after both world wars, the demand for non-central/non-high density housing took off with the post-war economic booms. The first set was closer to the pre-war housing that still held crafted elements even though much was mass-produced and/or built by less skilled labor. The second set was had a range of quality that had a larger element of lower quality materials and skilled labor. The third set started out of a higher qualtiy which fell off as the national economy faltered in the seventies. Still, whether expensive or not, quite a few of houses from all of the periods remain actively occupied and generally maintained.

Some comments regarding your comments. Brick foundations? Hmm. As to siding, I might think the difference in maintenance between lap board and vinyl would prove more beneficial to homeowners over the long term. There is a point where replacement of vinyl would prove beneficial, but I imagine most homewoners would defer that until absolutely required. The cost savings over the long run would have to favor vinyl though, in my book. Odd, but cul-de-sacs were meant to be the walkable neighborhood, friendly to pedestrians and children (unlike gridded streets which tended towards arterial/feeder usages and speeds.

In the end, I don’t believe that most people are going to give up their automobiles unless they have to. They like cul-de-sacs because they tend to be quieter with no thru traffic. They like to live where they feel comfortable, not where they are told they will be comfortable. And, they don’t perform cost-benefit analyses when deciding whether to stay in a home, or not. So, it’s my opinion that there is no upcoming crisis in housing in the donut townships, Pike or any other. Saying there will be indicates something to me, if you haven’t already guessed.

KurtL, this is a very good discussion. Some other thoughts on your comments:

assuming that there is a cost/benefit that a homeowner need assess, what explains the continued maintenance of such housing past what an analyst might consider a poor economic choice? Something else must be an overriding factor not explainable by money.

I would say there are two non-monetary things: 1) Emotions – People get extremely attached to their houses. My mom is a financial counselor and she sees family after family still paying a high rate adjustable upside-down mortgage that they can’t afford just because they don’t want to lose “their” house. She (usually unsuccessfully) tries to get them to dump the house and rent instead. 2) Sunk cost – Basically, they think, “well I’ve spent so much money on this place already, so I don’t want to abandon it now.” Economically, once your cost outweigh your benefit, you need to dump it. It is hard to do. Like Joe Smoker said above, a declining house just gets passed off to less invested owners and eventually renters.

Houses built prior to WWI were built better because the new owners could afford craftmanship. Homeownersship wasn’t in the cards for an overwhelming majority of Americans back then.

Unfortunately, at some point, we got this silly notion that home ownership was the American dream and everyone should aspire to it. That is part of the problem with the American economy and its current stagnation. There are excellent, high paying jobs in places like Oklahoma and North Dakota in the energy sector, however, most people are saddled with a mortgage and can’t migrate to where the jobs are. This will also apply to Boomer in the next decade or two as they are not going to be able to dump their suburban house to move to retirement communities, Florida, or walkable downtown locations. There are a number of good articles about this phenomenon called “retiring in place.”

Odd, but cul-de-sacs were meant to be the walkable neighborhood, friendly to pedestrians and children (unlike gridded streets which tended towards arterial/feeder usages and speeds.

Can you explain what you can walk to in cul-de-sac neighborhoods? You are right that they are friendly to children because there is minimal thru traffic, but nearly all require you to get in your car to drive to anything interesting – school, restaurants, grocery, doctor, hair appointment, work. Not my definition of walkable. We live near downtown Indy and we walk to work, I bike my daughters to school, we get groceries about a mile away, etc. We do have a car, but we only spend about $140 a month on gas (we spent $300/mo when we lived in Greenwood for three months).

In the end, I don’t believe that most people are going to give up their automobiles unless they have to.

But here is the thing: People already are. Vehicle miles driven has been declining since 2004 and the number of people under the age of 30 without a driver’s license has doubled over the last two decades. There will never be a day when the automobile goes away totally and everyone just piles into super dense cities, but there is already a pretty major shift afoot as younger generations decide they would rather play with their phone on the bus for 30 minutes than roadraging in a car for 30 minutes.

ahow628, I think a lot of this has to do with psychology, not economics. Many people are invested in a house for psychological reasons, as you allude to – emotion. I think you feel that a house is a financial investment, which it is for many people. For others though, it is an emotional investment in a place, which is more than just a single physical structure, I think. A home is the totality of house, neighborhood, schools and churches (for some). To leave it, one must overcome some subjective inertia plateau. One desires to move towards something else, or move away from something else. If some critical mass isn’t reached on a subliminal level, the impetus to move away doesn’t become an imperative.

There is no way for you or me to relate to the conditions that resulted in what we call suburbanization today. There was social pressure to escape the urban densities prevalent until World War I, and after the war there was the money available for more people to depart the central city for more peripheral locations with more space. So, if they could, they did. Funny, but most of the neighborhoods developed in the 1920s are today still considered “in townâ€, save for the rise of the (now excluded) Cities and Towns in Marion County like Lawrence, Southport and Beech Grove. I think collectively our problem was just a surfeit of land and the availability of transportation system that made travel economically feasible for many more persons than ever before (and I’m talking about interurban trains and streetcars here, not cars).

I cherry-picked that cul-de-sac remark out of Wikipedia. I do think that as originally conceived suburban neighborhoods were to be provided with sidewalks. Here, as in many places, it was left to individual developers to carry the original cost of infrastructure like sidewalks then roll those costs into the price of the lots. I imagine that way too many decided to forego that step, especially after the rise of the affordable car.

Are you talking about national statistics here, or Indianapolis statistics? As I would hope you’d agree, Indianapolis is a poor city for mass transit. I have a hard time associating those stats here. This is somewhat surprising considering how much more re-urbanized Indy has become since the 1970s. Indy should have better mass transit in the urban core, but those holding the purse strings have made alternate choices over the decades.

There could be a time where automobiles go away for the general population. If that happens, there will be a very painful transition period. Still, nobody listens. In the meantime, few are willing to give up the time or flexibility afforded by owning a car.

Are you talking about national statistics here, or Indianapolis statistics?

National. Most of the stories I read about this type of thing are from The Atlantic.

As I would hope you’d agree, Indianapolis is a poor city for mass transit. I have a hard time associating those stats here. This is somewhat surprising considering how much more re-urbanized Indy has become since the 1970s.

I definitely agree, however, I’ve managed to become much more reliant on mass transit in Indy. I live near Fountain Square and take the bus my girls’ school at 34th and Meridian a couple of days a week. I am luck that I work from home on my own hours so I can take the extra time required for the journey. If you want (or more likely, HAVE) to use transit, it is doable.

Indy should have better mass transit in the urban core, but those holding the purse strings have made alternate choices over the decades.

Adam Thies had another great quote at “We Are City”: “Our state struggles with knowing that we have a city.”

https://twitter.com/HolzmanLaura/status/370645799589249024

“Struggles”. THAT is an interesting interpretation on the rural vs. urban antipathy here in Indiana.