This is the second post in the series from citizens who support the Indy Connect Referendum:

As an undergraduate at Ball State University I participated in a summer-long study abroad in the summer of 2010 near Munich, Germany, and lived with a host family there. Not a day went by that summer without interaction with public transportation as my primary means of getting around – with some ease I might add. This was a lesson that stuck with me upon my return to Indiana.

In 2013, I was working as a post-undergraduate intern at the Indiana State Senate and the issues surrounding central Indiana public transit prospects were being discussed for the first time I had seen, per the introduction of a public transit bill. That session the language died, and I was sure why: Americans will never choose to use public transit opposed to their automobile, the service will be a huge waste of money, and taking away roadway for transit will just worsen traffic congestion – legislators knew these facts, too.

Fast forward to 2014; I began my Masters studies in January, and in March, public transit legislation was approved for central Indiana, and in May I was accepted for a graduate fellowship to study a German-American comparison topic of my choosing. Despite my first-hand experience of the usefulness public transit has to a society in another part of the world, I was still convinced in 2014 that transit wouldn’t work here. So, I decided to challenge myself and I chose to study German-American metropolitan public transportation as a comparison study for my fellowship. I wrote the report with the intent to describe how public transit costs and benefits can be objectively viewed. In other words, I include the “good†and the “badâ€.

To my amusement, the public transit literature for US cities is rampant with variation. The reason for this is the great freedom that exists within every State to develop public services as a direct reflection of how the State is able to organize itself politically.

That kind of freedom leaves a tremendous void in the societal expectations on how public transit relates to urban form in the US. Metropolitan regions study one another in the US for best practices in many ways that include public transit provision, but it is not possible to expect a pick of two random cities in the US to have similarly robust transit systems.

The result is cities in the US have moved forward with public transit expansions at different time periods and are therefore at different stages in development. The pro/con transit literature feeds off this disparity by producing reports that lack historical or demographical context. They fail to account for time, space, and path dependencies in the development of transit systems and the land-use policies required to support public transit riders. This is just something to keep in mind when individuals cite studies as the concrete, factual analysis they need to prove their point. It is accurate that some US transit systems operate poorly and have for some time, while others are very useful and have been for some time, but if you torture the numbers long enough, they will tell you anything you want to know.

In Germany, however, the development of public transportation from a societal expectation is far more homogenous than what is found to be common in the US. Citizens expect good transportation to be available across the country like the Deutsche Bahn regional train shown above near Munich. The reasons for this are based in political history, economic principles, and demographic differences. After the economic devastation of World War Two, public transportation services in many metropolitan areas were critical to the reconstruction process and were relied upon heavily for years afterward.

Later, when the country recovered and more people were able to purchase automobiles closer to the rates found in the US – which led to declining ridership rates for transit firms – the response wasn’t to tear up the infrastructure that existed for mass transportation like in most US cities during 1940’s and 1950’s. The response in Germany was to unify private and public transit firms in metropolitan regions behind the banner of public regulation in order to retain high societal benefits that ridership on public transit can create. The public organization model they used to do this has since been replicated in virtually all major German metropolitan regions. For a truly remarkable organization example, look no further than Berlin, Germany. Also a city-state, Berlin’s public transit system unites over forty public and private systems into a single coordinated regional transit system!

The benefits that German policymakers recognized were anchored in the reality that public transit is directly connect to land-use policy. That is, if a region favors more spread out development that requires more automobiles due to a lack of substantial public transportation options, the region is essentially favoring more growth in congestion. German policymakers also have implemented a drastically different tax and fee requirement on automobile usage.

The analysis is grounded in empirical evidence but the thought makes some sense intuitively; if public money subsidizing public transit infrastructure in the form of higher quality service and shorter vehicle wait times leads to higher public transit ridership around development, then maybe public subsidies to private automobile travel in the form of expanded roadways and ease of automobile ownership around development leads to higher automobile usage?

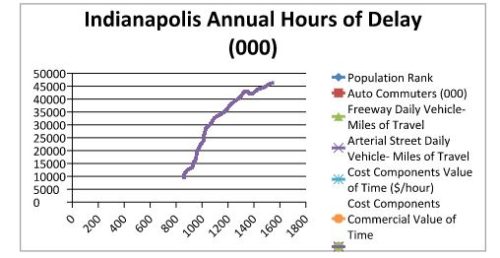

The graph below is derived from data obtained from the Texas A&M Transportation Institute’s Mobility Scorecard. It shows Indianapolis population growth from 1984 to 2014 on the X-axis in logarithmic form and increasing annual hours of delay on all roads on the Y-axis during the same period of time. As Indianapolis has grown in population, so too has congestion; but the connection to be made here is that that growth has been met with the scale heavily tilted towards road expansion and in turn leaves an additional burden of car ownership on different income groups in our region at different effective rates.

If one is willing to take a step back and think objectively about public transportation, you realize the debate ought not to be centered on whether or not public transit is useful, the debate should be centered on what the right balance is between automobile usage and public transit alternatives with accurate and un-biased information as to the specificity to the region. And this is exactly what is found in much of the literature in Germany; the sense that the debate is on how much ought to be spent towards public transit to achieve the benefits to society as opposed to whether or not the service alternative is useful exists. The debate on usefulness in the US is just one thread of literature; other threads include tax revenue versus expenditure equity towards financing public transit, political and administrative fragmentation issues, organization and service delivery, and supportive policies just to name a few. The need for accurate information is pungent.

Despite a vast picture the debate about public transit creates, it is my hope that the residents of central Indiana take seriously the opportunity to decide whether or not they feel the need to add better public transit to the region this year. There are plenty of deficiencies and lessons to be learned from around the world in the public transit sector. There will be challenges along the way, but the best outcome can be realized when we decide to move forward together. To try and find a mutually beneficial outcome should be the reach or, in other words, minimize the negatives and maximize the benefits of expanded transit options.

Ten months of researching, traveling to interview individuals, and writing provided me with a substantial backing on the economic and financial realities of how the sector operates. But perhaps the most impactful realization for me towards studying German-American public transportation was how it led me to question how public services are provided generally. The German Basic Law (their constitution) provides that the country establish public services that provide for equity in their provision. Essentially, the financing of public services is to be set up as to avoid excessive burdens on some taxpayers to the primary benefit of others. Our public transit plan isn’t perfect, but it would be a start.

Something to keep in mind that next time you pass someone that chose to use public transport on Meridian Street who has to sit on a bench next to traffic, or worse yet stand next to a pole in the grass or mud because the facilities aren’t there. Knowing now the full extent to which we subsidize private automobile travel here, as well as legislate low public barriers to entry for private automobile use, I’m not sure we should be then asking riders who choose to use (or have to use) public transit to pay taxes toward the service, the ticket price, and their dignity along with it.

It is my hope that we realize and understand in our region that there is a direct connection between quality of life and public transportation by saying, this is my city and I care about how it functions now, and in the future. As one of the most automobile centric cities in the US, perhaps some lessons can be understood and implemented on what we want the urban form to look like over the future decades. As someone that lives relatively close to downtown at the edge of the Old Northside Neighborhood, I’ve enjoyed reading about the history here, but I’ll be passionate about the future.

To celebrate the opening of the new transit center, IndyGo will be free for the week.

http://www.indygo.net/freerides/

My guess is that pretty much everyone (IndyGo, Indy Star, onlookers in general) will probably see this as a stunt. This is really depressing since any academic should seize this opportunity to study ridership during the free period.

I’d be very curious to see how the reduction in milling and resurfacing costs from road diets would compare to the $12M in annual revenue IndyGo takes in from fares.

Yes, the new transit center opens soon. And, yes, IndyGo will be free for the week. Is this a “stunt”? No. Is it a waste of taxpayer dollars? Yes. Will it do anything to alleviate traffic congestion in Indianapolis? No.

Let’s be honest here: buses are not an answer to traffic congestion. If anything, with the amount of space they take up on a roadway coupled with the number of stops they make (thereby backing up all of the cars behind them), not to mention the damage to roadways caused by these public transportation behemoths, buses exacerbate traffic congestion and other transportation problems in Central Indiana.

I am not opposed to reliable, efficient, and affordable public transportation in Central Indiana. But it seems to me that all of the fanfare behind the new transit center and additional buses on the streets of Indianapolis only shows how little work has been done in the entire region on the question of public transportation. It’s a Band-Aid approach, one that will not appreciably reduce reliance on personal automobiles by Central Indiana residents. And that’s sad, because Central Indiana (really all of Indiana) needs a reliable mass transit system. Further clogging of roadways with buses, however, does nothing to address this need.

AMEN!!!

I agree, but BRT is probably the best we can do right now. It operates on its own dedicated lane (no one will get stuck behind them) and since (I believe) state legislators shot down the possibility of rail-based transit in Indiana, it’s hard to say what else can be done.

The Transit Center is exciting, but you’re right, after all the ribbon cutting and PR around town we’ll be stuck with a big bus stop for years.

I am one of those who has been totally on board with the Red Line plan but has likewise started to question it.

What is the point of investing in mass transit if the city is not dense enough to support it? The entire Connect Indy plan will never work – the only way the mass transit in Indy survives (imho) is if dense, transit-oriented development grows around the Red Line and downtown.

If Indy was as dense as Paris, for example, we could fit our entire population (currently spread over 372 square miles) into the area between downtown, Broad Ripple, the White River and Highland Park. Imagine what mass transit would look like then. We could actually afford it and other services that would greatly improve the quality of life in our city.

This is where Plan 2020 and IndyRezone come in to play. Now that we can have transit-oriented districts along urban corridors, it will help IndyConnect succeed.

One must remember that the BRT and high-frequency lines are being planned in corridors where the density and travel demand already exists. Indianapolis-Marion County’s average density as a whole isn’t great, but that’s the average. One cannot look at the entire city-county’s average population density and then claim that BRT won’t work without the context of the characteristics of each corridor. The corridor planned for the Red Line is already the most densely populated in the city with the greatest mix of uses. The Washington Street corridor (Blue Line) has tracts that have higher densities but the average along that corridor is lower than the Red Line corridor.

You’re right in that dense, transit-oriented development needs to occur around the BRT corridors in order for it to succeed, and that’s where, as Kevin has already mentioned, the newly adopted zoning codes and Plan2020 come into play. The BRT lines anchor development and the new zoning codes allow these developments to be at least moderately dense and transit-oriented. We can’t expect transit-oriented development to take place without first providing the transit.

One point of clarification: I don’t personally see this as a stunt but that seems to be the consensus in the media and those speaking to the media. I wish it was a serious exercise in seeing what kind of an impact this would have on ridership. IndyGo takes a lot of taxpayer money but also hugely impacts people who need the bus system to get around. I was just saying that IF IndyGo were free all the time (losing out on $12M in fare box revenue) and if that reduced congestion and road space needed (and as a result the amount of maintenance $ needed), having IndyGo free all the time could be a net benefit.

As for congestion, it is a matter of geometry. Even at off-peak times (10am or 2pm for example), the buses I ride still have at least a dozen people riding which would likely be a dozen more cars on the road. Even three cars take up more space than a bus.

As for road damage, maybe, but if more people rode the bus, maybe we could get rid of more traffic lanes which reduces maintenance costs which would free up money to build higher quality roads instead of higher quantities of roads. Unfortunately, preserving the status quo (resurfacing) seems to be more politically palatable than reevaluating if the current infrastructure even fits our needs.

I can think of a few obvious benefits to the Transit Center…here are my top 3:

1. Lops off some of the unnecessary routing with the “bus rodeo”, and helps people avoid sitting in traffic or behind other buses. Every bus has its own bay and can be loaded and unloaded at its own speed.

2. It’s easier for IndyGo to provide security in a single location than spread out around downtown.

3. Real-time arrival displays. IndyGo obviously still needs to provide a smart phone application for real-time bus location, but not everyone who rides the bus has a smart phone.

It’s also a nice-looking structure and grounds that gives a former ugly surface parking lot back to the public by inviting them in. Eventually there will likely be a coffee shop or lounge.

It’s more than just a fancy bus stop.

Well stated, Mr. Kastner.

Thanks for the story, Brad. I want to share my experience. Like you, grew up in Indiana but learned about transit elsewhere.

For me it was Denver. I moved there in 1981 after graduating from Butler. Denver then was a lot smaller than it is today. There was no light rail. In fact, the bus system (RTD) was in pretty rough shape coming out of the recession of the 1970s but they brought in new management and vision and things were slowly starting to change.

I never dreamed I’d become a bus rider…I lived in the far suburbs but shortly after staring work downtown, my company’s HR department offered me a discounted bus pass. They didn’t just offer it. They strongly recommended that I take advantage of it, so I did. Interestingly enough, I worked for an oil company. In Denver, in 1981, oil producers were subsidizing bus passes. How’s that for irony?

This was before the internet, so I paid attention to what was going on while I was on the bus. Most of the people riding were like me which is to say suburban professional people. Think Carmel, Fishers, Brownsburg, Greenwood going to Lilly, Salesforce, etc. That was us. That was who was riding the bus in Denver in the early 1980s. Years later, when FasTracks came up for a vote, it was so those same people that RTD turned into bus riders a decade earlier who said “we will pay you to give us more transit.” There’s a lesson there for central Indiana, I think, if you care.

I think transit is a wonderful thing. It’s integral to me. I have used it across the US as well as in Calgary, Toronto, Amsterdam, Copenhagen and Malmo. I would have no qualms about using it anywhere else my travels take me. Currently, I only work with companies in cities with bikeshare and direct rail links from the airport to downtown (Denver, Minneapolis, Seattle, Portland, and San Francisco).

I worry about all the stuff I read about transit oriented development. I think there’s a very real risk when the focus is on city building people often lose sight of the core mission of transit…Dallas anyone? I believe that if you build a really great transit system (and great is not dependent on mode) then development will take care of itself. I saw that happen in Houston with the Main Street rail line. Amazing stuff…mostly organic.

Here in Ogden, I’m a ten minute bike ride from FrontRunner commuter rail. I can roll my bike on the train and ride off the other end, so if I have to go to Salt Lake City, Provo or anywhere else along the Front I never drive. I can even ride my bike all the way to the airport if I want and leave it in a secure parking area. My driving days are over.

But it didn’t just happen. Way back in 1981, I was the typical Indiana boy who just assumed that I was going to drive everywhere. all the timeThe reason I changed my mind was because a world class transit organization (RTD) made it easier for me to choose transit than to drive. That’s IndyGo’s job. I hope they’re up to the task. I question whether they are, but I truly hope so.

Thanks for your perspective Bob. It is an interesting position to be in; to observe other systems and use them day to day really makes you reflect. For me, part of the reason I chose to take a look at transit for my masters was the disparity in the service elsewhere compared to what I saw in my home state. And I agree with you about the TOD conversation – I make an argument that although transit is extremely wide ranging, one of the main focal points ought to be ridership and good systems will coordinate with development over time to improve efficiency.

Have you had a chance to look at Glenn Yago’s book? I’d be interested in reading some of your thesis, if it is finished.

I read Yago’s The Decline of Transit early on. One of the first items I researched was how the US got to where we are today and did the same with Germany. I’d be happy to share the report with you, it has been finished since May.