It is a popular pastime here in Indiana to complain about property taxes and their effects on the local economy. In the minds of many citizens, these taxes are levied on property owners and appropriated for wasteful pet projects and high administrative costs. But that’s just flat-out wrong, as property taxes provide citizens with the most important public services in the US.

Well, I can’t tell you what the right tax rate should be nor can I tell you how the money should be spent, but I can tell you that property taxes should remain an option for cities to raise funds. Politicians, civil servants, and public sector employees work for the people, but only when their paycheck comes directly from us.

I worry that we are so averse to property taxes that we will end up paying only payroll taxes and taxes on economic activity. At that point, will our leaders try to increase GDP at any cost? Will we pay all our taxes through sales tax? Why would we want to give our tax dollars to a middleman and have them decide what our priorities should be?

If the public were to reject property taxes and payroll taxes altogether, then government would be financed by commerce and industry instead. At that point, would our local government still remember who they worked for? Do we really want free enterprise to replace the voice of the people?

Property taxes support the most important services that local government provides including education, healthcare, and emergency services. While the Indiana legislature is busy considering property tax reform, please remember that capping property taxes does not reduce our government, only our control over it.

One final consideration, and the reason I raise the issue on this website, is that property taxes encourage economic activity and property development. Property taxes discourage land-banking because owners need to make a profit on the property quickly. Unlike sales tax or production taxes, they do not penalize additional production or commercial activity. Not only do property taxes provide a stable source of funding for government services, they force the highest and best use for property.

If anyone is looking for more information on property tax revolts and why they are becoming more common, see Urbanophile’s recent post here.

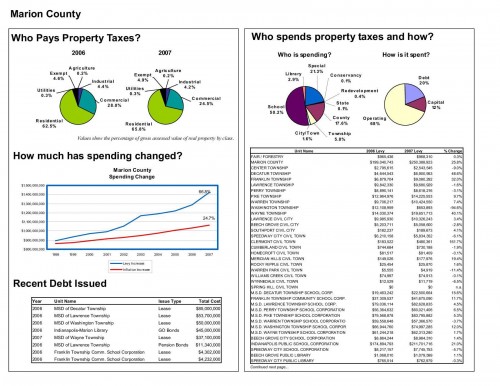

good write up. I think the problem most have with property taxes is that they historically have been increased consistently, at the will of those spending the money. Doesn’t seem to be any level of responsibility from those spending the money/raising the property taxes – when they run out of money they find a way to raise the taxes. From your chart, the schools are a great example. IPS, with consistently declining enrollment and poor management, has the highest increase of the schools. Good luck voting out school board members and having any impact. Their election happens at the time of lowest voter turn out.

I really enjoyed this piece.

I remember reading somewhere that the revolt over property taxes is largely a result of baby boomers aging and lobbying to shift the tax burden onto others. Especially with schools, it’s difficult in boomers’ minds to understand why they’re paying taxes for a service that they don’t immediately benefit from.

Andrew, I don’t think the “baby boomer” argument is the driving force in Indianapolis’ tax revolt of 2007.

Some of the older, stable middle and upper-middle class neighborhoods of the “old city” (Broad Ripple, Meridian Kessler, Butler Tarkington, Irvington) were formerly assessed under standards that included age of structure and didn’t take account of market value. As relatively old houses, they were “under-assessed” compared with newer suburban structures both inside and outside Marion County. So this resulted in low property taxes in those neighborhoods relative to selling prices. Nobody objected because this relative subsidy allowed residents to pay for private or parochial schools instead of sending their kids to IPS. But in 2004, the “market value” standard of assessment took away the benefit of living in an old house. Property taxes in Meridian Kessler doubled or more pretty much across the board. However, they weren’t yet outrageous. They were comparable to the suburbs.

It was the 2007 reassessment that did it. The previously-doubled property taxes then doubled or tripled again. The tax rate was then 3-4% of assessed value, so a $250,000 house was hit with property taxes of $7,500-10,000 depending on township. The homestead exemption had a dollar cap, and didn’t provide much relief.

When you consider that most formulas consider a house “affordable” when it is up to 3 times their annual household income, some quick math shows that the property taxes on that $250,000 house would amount to about 10-12% of the owner’s income…if he/she had bought the house for $240,000 based on an $80,000 annual income.

Now consider that most folks in those “stable” neighborhoods tend to live there a long time. They might not be able to buy the same appreciated house today, as people’s income does tend to level off mid-career while their property value keeps growing (well, pre-2008 it did; those neighborhoods I named actually had above-average appreciation). So even though they are still working, and living in a $250,000 house, their household income might be in the $60,000 range and they might have paid $180,000 for the house 10 years ago. Regardless of the fact that they have a big chunk of equity, the property taxes are still 12-16% of income.

In short, property taxes on the same house went from good to understandable to outrageous in half a decade.

Hello tax revolt. The governor’s mansion just happens to be at the boundary of Meridian Kessler and Butler Tarkington, and I’d wager that the governor realized he could never be reelected in 2008 if he lost Indy…which he would have done if he’d lost the older, stable, neighborhoods. By 2007 those neighborhoods were well-populated by GenXers (1964-82) most of whom were then homeowners in their 30s and 40s.

Hello tax caps.

I agree that specifics to Indy probably had more to do with it for our own local market, but I was referring to revolts against property taxes in general across the nation. Many markets are facing objections to property tax increases, which seems to me to be a macro-level effect and not a location-specific effect.

I’m sure that the economic downturn didn’t help things, either. Raising just about any kind of taxes during a downturn is pretty much political suicide.

Part of the problem was how they went about it. A friend of mine lives on New Jersey in the 58th street area and he was talking about it recently. Their taxes went up by 300% and while he admitted that they were probably paying under what was considered fair, being expected to jump up by that much is a lot to ask of people. Perhaps if they phased it in to the higher target over a period of time, it would have lessened the sticker shock.

I agree with all the comments so far. I think the state should have found a way to slow down the increase in tax assessments. I don’t know how I would have managed such a huge increase in taxes if I was on a fixed income.

But in the end, I still believe that property taxes are the right way to fund city spending. Just because Indiana and Indianapolis executed tax policy very poorly for a few years doesn’t mean we should rewrite our state constitution on a whim.

Graeme, I agree with you and Curt: the phase in of market-value taxation was handled very poorly. The unknowns followed by the sudden impact definitely contributed to the outrage. And Curt, you don’t have to be on a fixed income to have trouble coughing up an extra $250-500/month in taxes all of a sudden, plus extra escrow to your mortgage company. I’d wager that most working people don’t have that much flex in their budget on an immediate basis.

Graeme, I didn’t address your policy suggestion in my earlier response. I agree that property taxes should be part of the municipal-services funding of any large city. I do not agree that caps are a bad idea. What is a bad idea is that in return for caps, we shifted the local property tax burden to a state-replacement system where the state kicks back a portion of the now-higher sales tax to local units of government. We essentially went from a City-County Council of 29 to a super-council of 150 (the entire Indiana Legislature) determining city revenues. Bad policy, especially with the often overt anti-Indianapolis bias of the suburban and outstate legislators.

Further, in a state capital that also has a significant “eds and meds” complex, a significant part of the property base is tax-exempt. And a significant portion of the folks who work and pursue entertainment in the city are suburban residents who contribute only the penny sales tax on restaurant food to the city’s stadium and nothing otherwise to the city’s fiscal well-being, yet they consume municipal services (roads, streets, and sidewalks; water and sewer infrastructure; emergency services) daily. Forcing city residents to “carry” significant regional and statewide benefits through property taxes alone is unfair and unreasonably burdensome.

The most recent number I’ve seen is that 45% of Center Township property is tax exempt. Seems high until you consider federal, state and local government facilities, the two universities (IUPUI and Ivy Tech), White River State Park, city parks, the interstates, the Canal, all the various museums, and the plethora of state, regional and local non-profits (Clarian/Methodist, Wishard, Indiana Association of Fill-in-the-Blank, Scouts, Goodwill, Salvation Army, Gleaners, Wheeler Mission, Indiana Sports Corp., NCAA, the national sports organizations, etc.)

What is missing from the local taxing arsenal is a LOST (local option sales tax) and a NRIT (non-resident income tax). Each could help to capture payment that covers the benefits gained by currently free-riding suburban residents and to replace tax-exempt property in the tax base. And it also seems reasonable that since state facilities are concentrated in Marion County, there should be some payment in lieu of taxes by the state to recognize that fact.

I would be highly opposed to a non-resident income tax. It would create an incentive for existing businesses to leave Marion County and for new businesses to locate outside to begin with. I don’t dispute that some sort of regional tax solution is justified, but not that one.

John, I’d say that the perceptions of IPS and crime are more than enough excuse for those who want to locate or relocate outside the city. I don’t think a small wage tax is going to drive that much change, nor keep people from considering Park 100, Keystone Crossing, Castleton, Lawrence, and other Marion County township/suburban areas.

.

I’m mindful that Philadelphia had a HUGE commuter tax, several percent, and it did drive suburban office flight and development in the 70’s, 80’s, and 90’s. But the city isn’t exactly hollowed out, either.

.

What I have in mind as a regional solution is that commuters would pay the same income tax rate as residents in the county where they work. Currently that’s 1.6% or so for Marion County and lower for most of the suburbs, around 1.1-1.2%. The full amount of the “home” county tax would go to the home county, but the difference would be paid to the “work” county by the state (because the state collects the local income taxes). The suburban-county residents who do not work in a higher-tax county would probably act to prevent their county government from raising the “home” tax too high, preserving Marion County’s slight gain.

Even with all of the tax exempt entities here in Indianapolis, Indy citizens still subsidize the rural parts of the Indiana:

http://www.ibj.com/study-urban-tax-money-subsidizes-rural-counties/PARAMS/article/15690

We definitely need some regional cooperation.

Property taxes have two big disadvantages:

1. They are unstable because they lead to periodic tax revolts; no tax is more widely perceived as unjust as one that is totally unrelated to your consumption or ability to pay.

2. Moreover, property taxes gut local autonomy, since state governments are more likely to interfere with property taxes than with other taxes.