Have you ever been to an old downtown and marveled at the historic buildings? Have you ever wondered how they could create such beautiful buildings on such small budgets, compared to the placeless architecture we are told is barely affordable today?

The truth is that those multi-story, mixed-use buildings lining the street were built by a different culture. We are a different people now, and we demand different things from our built environment.

But that old American culture was a very clever one, and we can profit from studying what they did right, and how they did it. So here is their basic recipe:

1. Leverage small investments

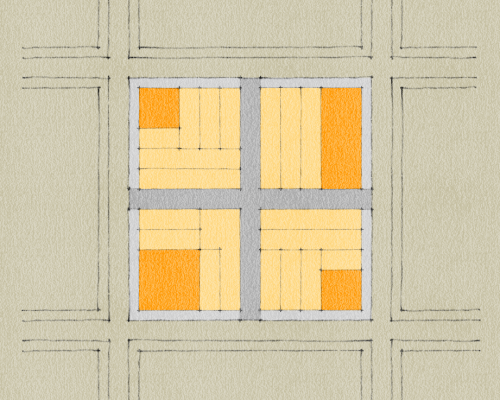

The typical traditional urban building is between 20 to 40 feet wide, and between 60 to 200 feet deep. This small width was a product of structural engineering limitations. A traditional building with masonry walls and wooden floors could not span further without significant cost increases, and tax policies often charged by street frontage instead of square footage. The result was small frontages and deep buildings.

The overall effect of a traditional streetscape is like walking through a well-curated art exhibit, where people can admire the buildings or the products in the glass storefronts. The density of different buildings and stores satisfies the pedestrian’s need for visual interest. It is a key part of what we call “walkability”.

Perhaps even more importantly, the small sizes encouraged ordinary citizens to become developers. Many buildings were financed directly by business owners or residents, who would offset building costs with lease income from unused spaces. These self-developing streetscapes ensured that no single developer or architect controlled the evolution of the city. It would reflect a social, shared history instead.

This is what made historic downtowns beautiful in a way that no government or philanthropist could recreate today, and why historic preservationists nurse a broken heart with every lost structure.

2. Share with your neighbors

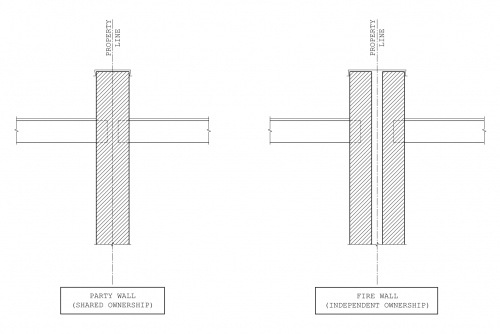

The party wall style of building, where adjacent buildings used the same structural wall to support their floors, was a very important money saving technique in traditional buildings. From the dawn of human civilization we have been building cities by slowly adding onto the existing structures. However, new construction codes that strictly regulate fire safety have eliminated this technique, and for all intents and purposes party walls are no longer in common use. Every building is now an independent structure.

The change has been beneficial in terms of life safety, but the effect on older buildings has been onerous as owners were left with a complicated legal situation just when downtowns were under fierce competition from the suburbs. The results are plain to see in downtown Indy, where adjacent buildings were torn down for new parking lots and the old walls still bear the marks of beam pockets.

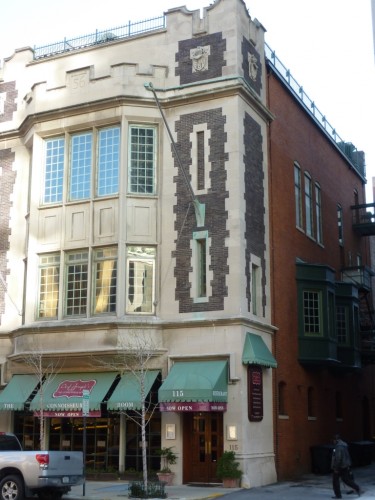

When we lost party walls, we didn’t just lose an inexpensive way to build. We lost an inexpensive way to live. A traditional building with party walls on either side will only have exposed facades on the back alley and the front elevation. There are two benefits: reduced heating costs and reduced facade costs.

The heating and cooling issues are simple enough to explain, because there are fewer pathways for heat transfer (assuming your neighbor is also climate controlled). This results in a significant savings compared to independent buildings with 4 exposed walls.

The construction costs are also lower, because only 2 facades must be weather-proof. The owners typically used the savings to invest in attractive architecture with architectural flourishes, since it made business sense. The corner buildings, with a higher burden of exposed facade costs, would naturally attract more profitable tenants. The loss of a corner building is the ultimate way to devastate historic districts, because there will never be a profitable way to replace what has been lost. The economic conditions that created those buildings is gone.

3. Build up, not out

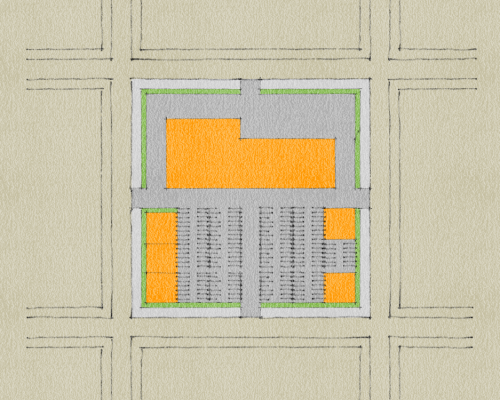

Traditional buildings, and traditional streetscapes by extension, never happened overnight. They evolved over time, as each small plot was filled in and then raised upwards. The neat thing about masonry walls is that they can support an incredible amount of weight if they are braced at each floor level, so adding a new floor on top was usually a simple process. This gave owners the ability to start small and incrementally expand their property as needed.

Here in Indianapolis you can see this evolutionary process frozen in time. The old streetcar stops were the commercial areas for each neighborhood, and as you travel towards downtown you will be traveling in time. On the outskirts of the old city limits, you will find buildings that look like 1-story general stores, but maybe just a solitary one or one that was converted from a residence. A bit closer in and you will find a healthier pocket of commercial buildings, some with 2 stories. Look closer, you can usually find where the first buildings were upgraded from 1 to 2 stories. A change of masonry, architectural style, or apparent age will show. Sometimes it’s easiest to spot in the rain when the masonry takes in water at different rates.

The closest neighborhoods will have fully formed commercial streets with 4 or 5 story buildings, which were the final stage of traditional building evolution until the invention of the safety elevator. This incremental development paradigm was a very cost-effective way to establish a business district, and also very different from our current style of development. The “build at once” streetscape phenomenon is a recent invention, and only necessary because of the presence of parking requirements.

Minimum Parking Requirements, whether for permitting compliance or loan approval, have been the single greatest enemy of the traditional building technique. The need for parking spaces based on square footage means that adding an additional level to a building requires more parking. And in an urban area, land is a limited resource. Building a parking garage is far too costly and complex a process when considering the needs of so many varied businesses on a single street, and so the only solution is to close the business and relocate where land is plentiful.

Lessons to Learn

As you can see, traditional building developers used their limitations as advantages, making the most out of known technology and social behavior. It is up to us to figure out how to apply these concepts to our modern urban areas. But the key lessons here are to create a development environment where buildings can start small, expand gradually, and create mutually beneficial relationships with their neighbors.

I particularly like the idea that “ordinary citizens become developers” and the idea of incremental growth and redevelopment.

Placemaking plays an important role. The adjacency to public space, transit, retail, or employment is important as a catalyst to develop around a space or along a corridor. Your mention of the historic Indianapolis streetcar commercial nodes hints at this.

I like that you’re thinking about this and appreciating how smart we were. Not only that, how beautiful our buildings were intended to be. Something we don’t pay much attention to these days it seems. Of course, not all historic buildings in city centers are small, however. Sienna, Italy, for instance, is crammed with 4 and 5 story buildings from the 900s 1100s a.d. But the party walls and attention to the street, and attempt at beauty are there even then.

It’s interesting you mention Siena because I had that in mind when I wrote some of this. But my photos were pretty horrible so I didn’t have any to share. But that’s a great example of a city that slowly evolved piece by piece and is now a World Heritage Site.

As you point out in your article, not all the changes are bad ones. Increased fire safety through modern construction means that a fire in one building of a commercial district will not necessarily burn down the whole block.

I’m curious how folks imagine we’ll turn back the clock on changes in scale in commercial real estate and retail. Everybody loves “low everyday prices”, but the only way to get them is in 120,000 square foot supercenters. So much cost of scale is externalized that a self-contained “small-build” is not really economical or particularly sustainable today.

Exactly. Even affluent consumers will bring themselves to shop at walmart, not realizing that you lose something when doing this.

Walmart’s economies of scale are intimately related to free roads.

Truckers do pay some taxes, but not on a per-mile basis. The vast bulk of their taxes are the gasoline tax — in other words, the same tax that every other driver pays — despite the fact that heavy trucks cause proportionally much more damage to the road than small cars. (The figure you hear is one 80,000 lb truck does as much damage as 9,600 normal cars, though that estimate may be out of date.)

another reason that storefronts could be more interesting (read ornamented) is that labor was MUCH cheaper than today. Re: party walls…I have also of course noticed the empty floor joist pockets on exposed formerly common walls, but if the buildings went up as described in this article- separately, how is it possible to create the situation where two buildings’ floors were carried by the same wall? I think it is more plausible that the bearing wall of a torn-down building is just left up when the rest of the building is removed.

“So much cost of scale is externalized that a self-contained “small-build†is not really economical or particularly sustainable today.”

So the question is, how much longer can we afford those externalities? Most suburban cities have already mortgaged themselves to the hilt on round two of their infrastructure and gas is still dirt cheap compared to the rest of the world. At some point, Walmart is going to get a bill for all the infrastructure they use and one of two things will happen – 1) Walmart leaves, city goes under or 2) Walmart pays up, prices rise. In either case, those more expensive downtown buildings/locations are going to reap the benefits.

Jacob and ahow, I understand exactly what you are saying.

But the world today is what the world today is, and there is a huge overhang of investment in the status quo that I believe will prevent significant macro change for at least another generation. (GenX is hyper-invested in the ‘burbs; Gen Y isn’t yet.)

For heaven’s sake, we’re SOOO progressive in Indiana that we’re still arguing about chiseling a gay-marriage ban into the State constitution. In this environment, a VMT is pretty far out beyond the horizon. Walmart won’t get that bill in my lifetime.

Again…please do not take me as an advocate for the status quo. I am simply a realist, unwilling [pardon my vulgar wording] to piss into the wind for very long, and not very fond of myself or others constantly whining about things that won’t change soon.

I change what I can and live with the rest, which is why working at the neighborhood level is so satisfying: I have a lot better chance of working with others and/or putting my money to work to change something significant in Irvington or on East 10th Street or North Meridian or Pendleton Pike than I have of building “The World According to Chris”.

The entire system of development and building was different 100 years ago. Growth and building were more localized.

McMansion-ize, Suburban-ize My City Part 1: The Reason For Homogenized Development and Mega-block Blank Walls- http://www.chicagonow.com/make-no-little-plans/2013/01/mcmansion-ize-suburban-ize-my-city-part-1-the-reason-for-homogenized-development-and-mega-block-blank-walls/

I’ve also thought about this issue that you’ve highlighted here and thought it to be such a travesty that we can not develop like this anymore. Excellent article highlighting many of the modern issues as well as the historical contexts that permitted such development. At this point I guess it will be up to local authorities to create new or amend regulations to promote such development. I doubt it would result in any changes or improvements to our modern building practices though.

Up here in British Columbia we have just amended our Land Title Act that now allows for party walls to be utilized again. But the problem (as I understand it) is that it is only been amended to reduce conflict between ownership and liabilities related to shared walls, not to promote the cheaper and older building techniques that you highlighted. So strata ownership issues resolved, building code and economic disincentives not so much. I guess in the end public safety related to fires and earthquakes trumps promoting economic benefits for builders. In the end that’s proper due diligence exercised by officials.

That’s too bad for human scaled architecture and communities though.

This is the exact reason why abandoned cities need to be looked at again. They hold immense possibilities for future businesses and residents. Don’t let them rot away.

Excellent article, Graeme, as I expected–but not the conclusions I expected you to draw, which made me like it even more.

The “scar” photos reveal the new generation of incremental change–a dismantling of what we easily added incrementally years ago. It seems that much more incorrigible because subsequent owners often add windows in what would have once been the party walls. These windows now offer the luxury apartment/condo owners views…of a parking lot. And the very fact that the surviving building has side windows where another structure once stood helps culturally to stymie the likelihood of new infill development. After all, the dweller at the side wall doesn’t want to lose his/her access to natural light (and that parking lot view) to an adjacent building! It offers just another nostalgic justification for bona fide party walls, where presumably such controlled demolition wouldn’t have been possible…or at least would have been a whole lot more difficult.

Just wondering, the last photo of the nearly vacant strip mall looks like the one on 86th street just before the Keystone on-ramp near Keystone at the Crossing but the text underneath says Carmel. Is this a different strip? Great article btw, interesting points. I think it’s interesting how certain areas have new attempts at revitalization that differ. This article made me think about the buildings that’ve been built on east 10th which almost seem like a retro attempt to imitate the one and two level storefront style compared to Eagledale/Lafayette Square’s use of old strip malls by small business owners and also the Westlane/71st area. I’m not a great fan of strip malls either, especially with Lafayette Square’s sea of empty parking spaces, but I do like the re-use of cheap spaces that seems to be going on and would seem to be cheaper for local businesses in some of these areas. Definitely don’t need more strip malls though.

It’s not surprising you would think it’s there, or anywhere else really. It’s a great example of placeless architecture. This example was taken from the north elevation of a strip mall in Carmel near the intersection of “AAA Way” and “Station Dr” near the Marsh grocery store at 116th and Keystone.

In the case of Walmart, let’s not forget that those “everyday low prices” are only possible because of the “everyday low wages” they pay their employees (excuse me – “associates”)accompanied by “everyday low benefits” tah force many onto food stamps and welfare financed by our tax dollars. Meanwhile the Walton hiers are worth about $26 billion each. Let’s also not forget the tens of thousands of mom and pop family businesses that used to occupy those wonderful old main street buildings your pictures illustrate so well, and that were put out of business by Walmarts “low everyday prices”. And while we are at it, let’s not forget the $3 a day Chinese workers who make it all possible.

Although there is a growing trend in the U.S. towards living and rebuilding urban cores there needs to be a alternative financing venue and the ones that are in existance need to be much more publisized.

In a era of many U.S. Citizens unemployed, under employed, home foreclosures and the fact that there are several large older U.S. cities that have lost significant amounts of there populations there should be a system of voluntary population shifting and a person with no or poor credit should be able to purchase older and even vacant buildings with zero down and virtually no finance fees.

This would be a system of the federal government paying up to $800.00 per month up to 10 years for any person renting or buying a bulding in which to live in regardless of income, this would benefit all levels on the socio-economic levels and the government would in turn recover it’s payout in the form of tax revenue.

This is a radical approach but would actually benefit the masses as opposed to relying upon the big banks and large corporations.

Well, historic buildings were build to last. Their simplicity but toughness always amazed me. This is one of the reason why I like UK architecture. Or Berlin. The old and the new works perfectly in there. But you are right; USA needs to learn from these examples. However, that´s our history. We don’t have that long historical tradition. Apart from amazing architecture in Chicago (Palmolive building).

Usa and Canada is still too modern. You raised some very interesting points. Modern trends in architecture are all about safety and eco – friendly materials. It´s meant to shock, to be original and to be sustainable. Sometimes it works as in Le Corbusier´s designs. Some time before I was trying to collect the best modern architecture has to offer in North America. Unfortunately, I ended up with the ugliest buildings in USA and Canada. Still, I love when someone can find a symbiosis between old and new. That would definitely be my preferred architecture style.

Great article about the economy of means in traditional urban buildings. I am encoraged that there are a growing number of jurisdictions that understand these issues and are working to chip away the modern impediments to this sort of development. These cities and towns need our help and encouragement – and investment!

The economies you’ve pointed out are still achievable if/where municipalities facilitate them, especially in old parts of town, but also in new development if it’s carefully conceived. Even Walmart has figured out that smaller-format stores make business sense in some places – even within their gargantuan business model, and they’re deploying 5,000sf stores in downtowns.

Sprawl is going to continue, sure, but traditional cities are coming back at the same time; thankfully, it’s not an either/or proposition.

How does the party wall prohibition relate to town houses, including newly built ones? Fire would be a greater threat to life because people are sleeping. Why wouldn’t modern smoke alarms and sprinkler systems virtually nullify the danger of fire in party-walled shopping streets?

I was wondering about this too. Are party walls not solid brick? How would fire get from one storefront to the other? Are there holes or something?

Here’s an explanation I used elsewhere, should have posted here as well:

The issue with shared party walls is that a collapse on one side will bring down both buildings. The fire walls remove this danger by making each wall an independent structure, so a collapse on one side will not affect the adjacent building.

Party walls are allowed in certain conditions such as similar uses on both sides of the wall, but the two “buildings” cannot be considered as separate and are treated as a single structure in building codes. The older buildings with existing party walls, such as those discussed here, are “grandfathered” in and allowed for continued use, but they cannot be improved without meeting current codes, unless the building code for that state makes an exception.

Horizontal fire barriers are required in skyscrapers as well. For example, if you have a parking garage below office spaces, then a rated fire assembly must exist between the two uses.

I’m sorry if the article caused any confusion on these points, it is a complicated issue and each jurisdiction has different rules so it’s tough to generalize.

I would also want to consider permitting issues as major road blocks…

I live in downtown DC and have looked into renovating my own Victorian row house as well as a few others in the neighborhood. It’s nearly impossible to do what my grandparents or their parents did while building. I’m not sure what it’s like elsewhere, but EVERYTHING in DC needs a permit. Want to change a sink (legally)? You need a master plumber to sign off. Same goes for adding an outlet. Both those tasks have almost no physical costs, and only take nominal labor. Those signatures usually cost several hundred dollars, plus the permit costs. Add in the time to get everything and suddenly a 2 hour, $30 DIY weekend project has become a $500, 30 hour process that requires several days of vacation time for day-trips to offices that are only open 9-5.

…and that’s just for the easy stuff. Don’t even think about putting up a wall, adding a porch or roof deck, or a pop-up. In a historic neighborhood? Great. Now you’ve got to get a building permit that follows one set of rules, a zoning permit that follows another, and a historic approval that follows a 3rd set. The rules don’t have to overlap and often contradict each other. There’s no mechanism to get the different boards to work out their differences. It’s a nightmare.

Great piece! thank you

Excellent post… Thanks! One other thing… Because Main Street buildings usually had such simple massing they could be used for many things over time. In a town’s most prosperous times, they might be retail with offices above. In normal times, the upper levels could be mostly residential. In times of decline, the street level might go to offices, then residential, then maybe even storage at rock bottom. But because the buildings had some use all along, they would not be torn down, and could be renovated when the town turned up again. Not so for a standalone Burger King, which could never be anything but a fast food restaurant.

I you think of the shops inside an enclosed mall as “buildings” and the walkways as streets, and the food court as a town square you see that this human scale architecture exists in every suburb. It is only snobishness that blinds people from seeing this.

https://plus.google.com/117587286352893114697/photos?hl=en

Too bad you have to drive to the artificial “urban walkable environment.” I don’t think it is snobbish at all to exclude malls from the category of “traditional buildings.”

The row houses in New York, Chicago, and Baltimore are timeless. I would love to build replicas in downtown Dayton, Ohio where I live in a townhouse built in 1827. My home is freestanding, but we condoed the 8,000 square foot home into four residences.

We are doomed with inefficient land use patterns by our economic system that values shot term gain over long term investment.

A big reason we still get crap buildings—even in cities where there are no downtown parking requirements on site—has a lot to do with lending rules. You just can’t get money for a grand building because banks need to see a quicker ROI. If you’re a hot market and can cajole big developers to front more of their own money to build to a higher architectural standard (via design review), go for it. It likely won’t be the foot thick masonry walls and beautiful details of days gone by, but it’ll be better than the dreck that most Americans seem to tolerate!

Buildings serve several needs of society – primarily as shelter from weather and as general living space, to provide privacy, to store belongings and to comfortably live and work. A building as a shelter represents a physical division of the human habitat (a place of comfort and safety) and the outside (a place that at times may be harsh and harmful)..

My very own blog site

<",http://www.caramoan.co/caramoan-beach-resort/

Downtowns are brilliant place and space-making because they provide shelter, a distinct inhabitable scale, a street-edge, and provide definition and enclosure. They are of an inhabitable human dimension and scale. They define the space along a pedestrian-oriented street. Pedestrian access and convenience to retail and commerce, and community activities is enhanced. It makes sense to the user at street-level and provides safety. It is easy to navigate and orient oneself. The architectural and spacial theories you are speaking of are definition, scale, orientation, compression and release, prospect and refuge, shelter, boundary, and containment.

AND let’s not forget SOCIALIZATION versus isolationism.

http://www.format2000.com/1487eJQ6e39J9J61sYuP.html

http://www.wm-centre.com/iRv7iQ44ftLKw3LL758.html