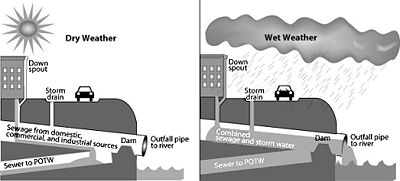

A little known or seen part of our every day built envrionment will be the focus of one of the city’s largest infrastructure projects ever in coming years. What is commonly called a “CSO” or “Combined Sewer Overflow” is a structure that was implimented in the late 19th and early 20th century. A single system of buried pipes were used to collect sewage and storm water runoff so that surface pollution was eliminated. At the time, this was thought to be a great improvement over the current systems. However, when the pipes were filled to capacity, there was nowhere for this combination of sewage and storm water to go. Outlets were built into streams and rivers. This lead to what eventually became our prior generation’s realization that this was a poor choice. The graphic below, sourced from wikipedia, demonstrates how the system works.

Fast forward to the present, and we are dealing with what is essentially a problem created by our forefathers. Think about today’s popular rhetoric about sustainability & “green” living and you begin to rapidly draw a correlation that there is a big problem with dumping raw sewage into our rivers. In Indianapolis, our main source of drinking water is drawn from the White River, treated and then sent out to businesses and homes around the region. This is done by two wastewater treatment plants on the south side of Indianapolis. In short, this is a huge problem. So huge that in 1994, the EPA enacted policy to require cities with CSO’s to begin addressing the problem and finding a way of dealing with it. This policy reflects the spirit of the Clean Water Act of the 1970’s.

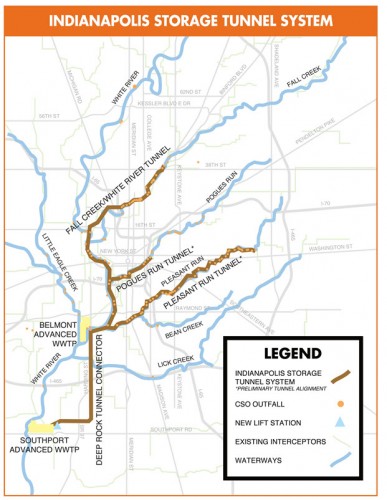

So how does this apply to Indianapolis? A very detailed account of how we got where we are, can be read here. Within the past decade, the EPA sued Indianapolis to “force” us into coming up with a way to improve the outflow of sewage into a number of regional streams and rivers. The city developed a long term plan for managing this problem. This plan, which was estimated in 2005 dollars to be $1.73 billion, would mitigate the affects of CSO into streams by constructing a system to hold the contents of what currently spills into the rivers and streams.  The system that was originally planned to be constructed, would consist of a large tunnel system 200 feet underground that would funnel a number of CSO facilities into it. Additionally a smaller capacity (relatively speaking) system of holding cells located 35 to 70 feet underground and linking the two area sewage treatment plants (basically a conveyence system) would be constructed. This system would contain 24 million gallons. This entire system would hold excess sewage and runoff in the event of a rain storm until either of the two facilities could treat and release the water back into the White River.

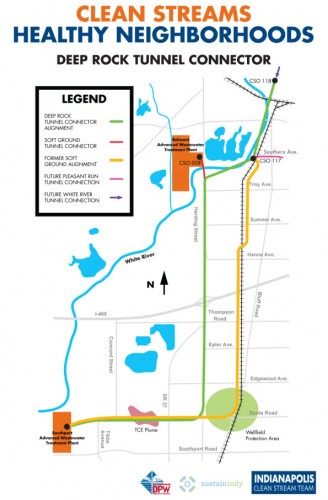

Recently, the city announced that through negotiations with the EPA, and a modification of the original plan adopted in 2006, that it would save $740 million to tax payers. The release by the Dept of Justice, details a plan that would eliminate this smaller inter-plant system by making it an extension of the deeper tunnel system as well as extend the large tunnel by 1 mile on it’s north end. By doing this, it will allow the capture of 2 CSO’s that contribute largely to the violations currently happening earlier than originally planned. However, it would push back the planned operation of this portion of the system by a year and some change. The trade off however, greatly expands the capacity of the system and the EPA agreed. The Justice Department claims a savings of $444 million. At this point, the difference between the Dept of Justice figure and the City’s figure is unknown.

The plan as it stands, will be a combination of tunnels that will have a holding capacity of  250 million gallons and be located 200 feet underground. The tunnels themselves will be 18 feet in diameter. The current overflow of 7 billion gallons a year of untreated sewage and storm water will be reduced to 414 million gallons a year. Bidding will conclude for the first section of the tunnel in 2011, which is called the Deep Rock tunnel Connector. The DRTC will begin at the Southport Advance Water Treatment plant and run to the Belmont AWT plant located on Indy’s southside. Four additional tunnels will be dug after this one has been completed. The total system is slated to be operational and compliant to the 2006 decree, by 2025. An additional website detailing the White River Tunnel portion, is located here. The City has a website detailing the system further here.

Criticism

At this point, some may be saying, why are we spending this much money and enduring sewer rates that will rise to pay for the system? For one, violations will be penalized by hefty financial fines by the EPA if nothing is done. The ethical side of not doing anything also looms. Do we want our children to be drinking sewage laced water? Of course not. This project must be done in some way, shape or form. Our current mayor, Greg Ballard, has taken strides to try and lessen the impact of expected rate increases. His plan to privatize the water and sewer by “selling” it to Citizen’s Energy is a step in the direction. By consolidating operations, a savings can be calculated to rate payers. Initial figures peg savings of 25% compared to initial rate increases. This is one situation where privatization of a public service seems reasonable.

People may also be asking why can’t we better engineer a system that collects and treats storm water naturally? We have started to see small improvements in this area around the city in the way of the Cultural Trail and it’s rain gardens. The recent Ohio Street Rain Garden project and other projects in the city have also addressed the storm water runoff issue. However, the need for action is urgent, and the deep tunnel projects will help to mitigate the environmental destruction currently being caused by our legacy CSO situation.

This is a classic example of doing things the wrong way and putting tomorrow’s generation on the hook for cheap decisions today.

These will be great for urban exploration if every built… the Pogue’s Run tunnel is already quite interesting already!

Well… if you don’t mind the sewage.

Note: all Indy’s intakes for surface-water treatment plants are located upstream of Indy’s CSOs. The Fall Creek treatment plant is at Keystone; the first CSO on Fall Creek is at the State Fairgrounds a half-mile south. The treatment plant just north of 16th (behind the UPS facility west of MLK) gets its water from the upper canal, which is diverted out of White River where the Monon and Westfield Blvd. cross the Canal in Broad Ripple.

So people in Indy don’t drink our own sewage. Mooresville gets that, downstream. (However, Carmel’s sewage treatment plant is just north of 96th on Hazel Dell and it discharges into White River…)

The EPA decree is all about implementing the part of the Clean Water Act that calls for our rivers and streams to be fishable and swimmable…safe for human consumption of fish and safe for human contact with the water.

Maybe my grandson will be able to take his own son to play or swim in Pleasant Run at Christian and Ellenberger Parks someday.

A relatively recent Economist detailed plans by NYC, Philadelphia and other places to use natural water collection systems in large quantities to greatly reduce the volume of need in managing runoff. Why can’t Indy do the same?

Trees Grow in Brooklyn: A natural form of relief for overworked city sewers, Nov 11th, 2010

http://www.economist.com/node/17468409?story_id=17468409